WHAT is expected of a good professional

actor? Probably the ability to convey conviction in any type of role, an

unquestionable mastery of his lines and just enough radar to avoid

bumping into the furniture.

For a good amateur actor, however, that's less than

half the story. You won't find him giving us the Lear of a lifetime and

then basking in the afterglow while sycophantic supporters insist on

telling him that he is every bit as good as he thinks he is. Not if he

really is a good amateur.

A good amateur actor is also a team player. He has to

be. He's the one who will take his bow, then step out of the spotlight,

remove the trappings of his success and set about clearing up the coffee

cups and ice cream tubs and putting away the chairs that have been newly

vacated by the village hall audience.

Amateur theatre is hard work. It involves far more

than the stuff-strutting that is merely the tip of the iceberg. Day jobs

have a tiresome tendency to eat into the time that could otherwise be

devoted to learning and rehearsing – time that is generously at the

disposal of the professional.

Moreover, a good amateur never forgets that the

lesser mortals by whom he is surrounded have been working their socks

off to provide a setting for his talents. Without them, his inestimable

contribution would have been a waste of time. It's no good calling on

winds to blow and crack their cheeks if there is nobody front-of-house

to rip tickets and let in the patrons, or behind the scenes to wind up

the tempest noise.

Professional theatre can afford the idiots who think,

however mistakenly, that they are God's gift – the people so preoccupied

with themselves that the perceived failings of their fellows make no

difference. But amateur theatre, involving people who are united in

their hobby, requires a team spirit that recognises that no role,

on-stage or off-stage, is more important than any other.

Take away the tea lady and questions will be asked in

the house.

It has, however, dawned on me belatedly that I have

been going off the rails in stating my belief that a good amateur can be

as successful as a professional in tackling anything except ballet.

Having watched amateurs who have mastered unicycling, juggling and

tightrope-walking for Barnum, I was pretty confident that the

world of theatre was their oyster.

I was peeved on their behalf when the impresario

behind The Witches of Eastwick insisted on giving the show a

limited try-out with a dozen amateur companies to see what sort of a

fist they made of it before releasing it to the ranks of the great

unpaid. After all, its essential requirements are four strong central

characters, three of whom have to be prepared to dangle on the end of a

wire. Oh, yes, and they have to be able to sing as well – although this

is habitually taken as read when any musical company is looking for

principals.

Amateurs, by and large, are talented people, which is why it is about time that under-instructed outsiders who give the impression of having discovered an unpleasant smell under their nose if they are confronted with a conversation about amateur theatre should be laughed to scorn for their stupidity.

These are the ignoramuses who assume that if an actor

were any good, he would have turned professional. They cannot

grasp the fact that whether he or she is marvellous or mediocre, the

stage is a hobby – just an adjunct to a job that is probably nothing to

do with theatre but which is nevertheless one that is enjoyed and

fulfilling.

Even so, I now realise, it is time to modify my

evangelism on behalf of amateurs. Enlightenment dawned when I was

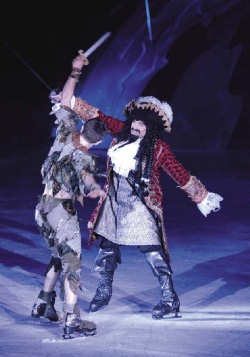

watching the Russian Ice Stars leaping and pirouetting in Peter Pan

on Ice, (pictured right) producing high-speed spins that yielded

heaven knows how many Russian revolutions to the square foot.

No amateur could have done this. Even if he had the

skills, he would also need a convenient ice rink on which to hone them –

not to mention the necessary bonus of belonging to a group that

presented its shows in a theatre that could turn its stage into a

temporary ice rink on cue.

For similar reasons, I now realise that I am unlikely

ever to see an amateur performance of Starlight Express. I have

seen amateur undertakings of all kinds that would have had no problem in

gracing a professional stage, but roller-blading would be a challenge

too far.

So in future, if anybody catches me saying that

amateurs can do anything, it will be because I have forgotten to add two

little words: Well, nearly.

John Slim

The hidden dangers of telling it like it is

YOU never know what's going to happen in the interval. Sometimes, I hope that the interval will be an improvement on what has passed so far. Sometimes, people ask me if I am here to do a review – at which point, I reply, “But of course! I never go anywhere for pleasure.”

That's not true, but it can offer a small smile on an awful evening.

Being a professional theatre critic involves what is called on-the-job training. You teach yourself. I have never heard of a course in theatre criticism. That's why you start by wondering what to write, and this continues until the happy day when you wonder what to leave out – by which time, your years of unselective theatregoing have conditioned you, both to the awe-inspiring and the awful.

People envy you your free seat and possibly the clink of the coinage that usually goes with it. They may not think of the sometimes frightening responsibility that is also in attendance – and which was forcibly brought home to me after I had made a completely justified comment on an actor's failure with the accent he was trying to present.

DWELL UPON EXCELLENCE

It has been suggested that a critic ought to dwell upon excellences rather than imperfections – and certainly, the result, I learned, of my not doing so was that the man concerned, while not exactly indicating that he proposed to try putting his head on a railway line, had been that he had talked of giving up his hobby altogether.

That was a shock. Criticism should always seek to be helpful, and in this case the inference was meant to be that he should in future avoid any role that required an accent. Unfortunately, it was not taken like that. It was not seen to be helpful at all. It had been seen as presaging the end of one man's world.

On the other hand, his reaction clearly indicated to me that abandoning his thespian pursuits would perhaps after all be a sensible thing to do. Surely no actor, amateur or professional, can imagine himself so perfect as to be beyond the need of a little help? It's people like that for whom the researchers for The X-Factor scour the country to ensure that the rest of us get a laugh in the early rounds.

After all, as actor Michael Simkins has pointed out, criticism may hurt, but being ignored is the greatest insult.

Sadly, one dramatist found out all he needed to know about being ignored. The late James Agate, doyen among theatre critics, went to sleep during a performance. When the playwright sought his opinion of his play, he told him, “Young man, sleep is an opinion.”

But criticism is a theatrical hazard, not only for playwrights and actors – for critics, too. It was Peter Ustinov who pointed out that critics spend ages searching for the wrong word which, to give them their due, they usually find.

DESPAIR OF THE DECIBELS

Years ago, I had the temerity to despair of the decibels coming from a band accompanying a show in Solihull, in the West Midlands. They were so loud that the three girls grouped round a microphone at the side of the stage in best backing-group fashion did not manage to get a single syllable past the orchestra pit.

And the response to my response? An anonymous letter saying that I was the only one in the audience who did not like the band.

Clearly, and before the writer knew about my still-to-be-penned remarks, he had fortuitously taken a straw poll as people were leaving. He was therefore able to assure me that the burghers of Solihull were looking forward to dancing on my grave. It was his way of paraphrasing Kenneth Tynan's bon mot, that a critic is a man who knows the way but can't drive the car.

Alas, his coyness about his identity prevented me from writing back to

him, but I did point out in a subsequent column that anyone who indulged

in such an energetic terpsichorean gesture at my funeral would possibly

have to retreat hot-foot, because I intended to be cremated.

But to revert to this idea of dwelling upon excellence – or rather, as is all too often the case when the review comes from too close to home, of finding excellence where none exists in case somebody gets upset. I always wonder, when I read one of these kind-to-everybody reviews, what the effect is on anyone in the cast who actually deserves praise and sees it showered in equal measure upon those who clearly don't. The natural reaction ought to be, “Why do I bother?” That is the person who has every right to be upset. As Gilbert pointed out, if everyone is somebody, then no one's anybody.

There is also the little matter of being fair to people who may be considering spending their hard-earned cash on buying a seat for a future performance – not to mention the stupidity of doing a rose-tinted review that makes any reader who was in the same audience wonder whether you were the only one there who failed to spot the imperfections and therefore on what grounds you presume to offer a critique.

No critic should expect to please all the people all the time – still less, try to.

John Slim

The Dudes who mix mirth and music

FORGIVE me, please, while

the Philistine within me comes to the fore. What I don't know about

opera would fill both sides of an elephant, single-spaced in

eight-point.

But if my senior daughter, who happens to be an accomplished amateur

singer with a well-honed sense of the ridiculous, tells me that I have

to go and enjoy The Opera Dudes because she and her husband have

returned hotfoot from laughing until they cried while seeing them in

their village hall in Hampshire, that is good enough for me.

Both are tenors – “showmen who really know their stuff”, she assures me – and one is “a fantastic pianist.” They appear, moreover, to be showmen who will shortly be in the Midlands under assorted labels – Mission Improbable, Duplicate of Mission Improbable and Licensed to Trill or, pictured right, as Neopolitan Tenors with songs you can't refuse.

Tim Lole was a chorister at St Paul's Cathedral and an organ scholar at

Trinity College, Cambridge, and Neil Allen has become an international

operatic tenor after starting life as a builder. They both decided that

becoming one half of a singing comedy duo sounded to be a pretty good

hobby. I found them on their Opera Dudes website, with a clip that

demonstrated their voices rather than urging me into hysterics – but

that is an aspect on which I am happy to take my daughter's guidance.

The voices, in any case, can fend for themselves: Neil launched his

professional career as a singer with the leading role in Cavalleria

Rusticana and has since been in the spotlight with Carmen, La Traviata,

Rigoletto, Die Fledermaus, Barber of Seville, Tosca and many other

operas. He trained with Magdala, the community-based musical

organisation in Nottingham where Tim became artist-in-residence in 2000.

They came under the wing of Magdala's artistic director Michelle Wegwart,

one of Britain's leading singing teachers. Tim has conducted most of the

opera companies in the UK after an early career that included a stint

with the City of Birmingham Touring Opera. He spent six years as staff

conductor at Scottish Opera, during which time he won the Donatella

Flick Conducting Competition at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London.

But now it's all this and comedy, too! I can't wait – especially if

Elmbridge Village Hall, near Worcester (January 31), matches Hampshire's

Soberton tickets at £7.50 each, which came under a scheme sponsored by

Hampshire County Council to bring culture, however lightly administered,

to the villages and included – back to my daughter – “a wonderful tea

with sandwiches and home-made cakes.”

There is something special about talented musicianship in comedy format. Think back to the tinkling pianos of Les Dawson and the inanely irresistible Victor Borg – and lie in wait for The Opera Dudes.

John Slim

Other venues that are on stand-by include the village or parish halls in Norton-juxta-Twycross, on the Warwickshire-Leicestershire border (January 29); The Shelsleys (March 13) and Hallow (March 14), all in Worcestershire; and Shipton, Much Wenlock (April 17), and the Talbot Theatre, Whitchurch Leisure Centre (April 16), both in Shropshire.

OVER these many years, I have

still failed to become sufficiently familiar with the seating

arrangements in

I usually opt for a spot on the

gangway end of a row, which undoubtedly assists my repeated voyages of

discovery – but if it is an aisle with half the row on one side and the

rest of it on the other, I am always handicapped by my uncertainty as to

which way I should be looking when I am peering for seat numbers in the

gloaming.

Even after a quarter of a

century of homing in on Hall Green Little Theatre, I still can't

remember whether the low numbers are on my left or my right as I enter

the auditorium and renew my acquaintance with the gilt cherubs that

adorn its walls. (I am sure there must be a reason for these overweight

infants, incidentally, but I don't know because I have never asked.

Asking is another thing I can't remember). In any case, the task of

finding and reading Hall Green's tiny seat numbers in the half-light

never promises a successful conclusion to my pilgrimage.

Highbury Theatre Centre, in

Sutton Coldfield, does not have a centre aisle – should that be a nave,

Vicar? – but I know that if I turn right after leaving the foyer to

climb the stairs at the back of the auditorium I will arrive at the top

of the aisle that offers immediate access to H1, I1 or J1, so I don't

have time to be confused.

Just to digress: why do brides

make such a big thing out of walking up the aisle? The central route to

the altar is the nave. She who progresses by any other route is in grave

danger of being mistaken as being a bit on the side.

But, getting back to theatres,

There is nevertheless a

drawback. The two entrances to the auditorium are clearly labelled 1 and

2, and every ticket is helpfully inscribed with the door number relevant

to its seat. Unfortunately, the Great Theatregoing Public either cannot

read or does not care. It enters in droves via Door 1 because Door 1 is

the first thing it sees on reaching the top of the stairs from the

foyer, and if it is seeking Row K then I am liable to have 26 of its

representatives filing past me in a series of brief flirtations with my

kneecaps, when half of them ought to have entered via Door 2 at the far

end.

A salute, therefore, to the

Grange Players, of

In my case, for my most recent

visit, it told me: “Row L, seat 9, right.” There was no need for me to

look even briefly to my left. I was safely in the care of a know-it-all

ticket – a sort of Playhouse sat.nav that surely deserves to be copied

by theatres and theatre groups, amateur and professional, all over

Give the Grange Players a medal!

John Slim

IT is not to be confused with

the Road to

It was going to be one of those icy

wintry nights that had been following the sunshine of bright and clear

days for quite some time. The Way to

Meanwhile, the Nearest and Dearest

clustered round, insisting that I was going to be armed with a flask of

coffee, a balaclava helmet, woollen gloves, a scarf and a box of cheese

sandwiches, plus a shovel from the shed. I was also reminded not to

overlook the car's mats and their anti-sliding properties when I was in

the apparently inevitable ditch.

I confess that I did not appreciate that

the role for which the sandwiches were being lined up was to stave off

slow starvation on the M 5 – which is why, wondering uncertainly why I

had been given them just before dinner, I sat down and ate the first

one.

Consternation! I had ensured that I

would now be going bravely into the unknown on depleted rations.

Moreover, having donned my gardening shoes for my snowy pilgrimage to

the garden shed in search of the spade, I was refused permission to

substitute respectable footwear for my journey. Good heavens, who was

going to study my feet, assuming I ever arrived? The N & D was

positively scathing.

Her caring self came back into play,

however, with her insistence that I had to take my mobile phone. This is

a grossly underused instrument, largely because I feel I cannot trust a

machine on which the red button means Go. It habitually lives on a

bookcase shelf, undisturbed and unconsidered – which is why, when it is

thrust into my consciousness every few months, it inevitably needs

charging.

This time, having seen it added to the

balaclava, the coffee, the sandwiches, the scarf, the gloves and the

spade, I extricated it from my overcoat pocket on arrival in the Grange

Playhouse's rough-hewn car park and temporarily overcame my prejudice

against pressing red for Go. N & D had to be told that the expected

thrills of theatregoing had somehow eluded me.

Unfortunately, the charging this time

had clearly been inadequate. I made a call that lasted all of three

seconds before cyberspace cut me off without my hearing any confirmation

that I had been heard in Bromsgrove.

All told, the Way to

I can't help feeling that

John Slim

The furtive world of hidden humour

IT had never occurred to me before, but there's a treatise waiting to be written – about hidden jokes.

I can't do it, because I am aware of only

three – and I can claim credit for discovering only two of those. My

granddaughter beat me all ends up in finding the other one. Having

recently watched a video of Father

Ted, she asked me a question that had simply never occurred to me:

where's the church?

And it's a good question, undoubtedly.

Father Ted and Father Dougal occupy a presbytery – that big, rambling

white house dominating our view of

Despite the distractions, the inglorious

threesome are presumably priests with a mission to the souls in their

care, and priests are usually able to walk more or less into their

church as soon as they leave their presbytery. Not this heroic trio. As

my granddaughter shrewdly observed, there isn't a church in sight. And

that, I suspect, is writer Arthur Mathews's hidden joke. The more I

think about it, the more I am convinced that he decided that his three

reprobates were going to be far too busy to be distracted by religious

goings-on.

And what's the betting that his next

thought was to wonder how long he could get away with it without anybody

missing the church? The last of the three series of

Father Ted was in 1998, and

they came to an untimely end with the death of Dermot Morgan, who played

the central role, from a heart attack at a party the night after filming

finished.

Eleven years later, it had still not

occurred to me that there wasn't a church in sight, and I had not heard

anyone comment on its absence until my granddaughter, newly unleashed on

the University of Birmingham, realised it was a little odd.

I'm sure it was not an accident. Think

priests, think presbytery, think church: it has a built-in

inevitability. Once you get to the presbytery, can the church be far

behind? Well, yes, on

In dispensing with the church, I am sure

that Arthur Mathews knew precisely what he was doing and wondered how

long he could get away with it. If 11 years is the answer, he has to be

content in the knowledge that it was an excellent joke – but one that

did not hide as long as Noel Coward's rather rude one.

This is a piece of Coward contrivance

which, as far as I know, remained undiscovered from the London opening

night of Blithe Spirit in 1941

until I stumbled on it early in 2009. Sixty-eight years is a long time

for a joke to stay hidden, especially if it is a clever one.

I found it because I had been bugged for years by the remarkable surname that Coward had given to one of his central Blithe Spirit characters, Charles Condomine. This is a name I have never met anywhere else and I could not help thinking that it was unnecessarily unusual.

From there, it was a small

step to break it into its component parts. What I got was

Condom in E.

E? Well, yes: Elvira –

Condomine's first wife, the one who returns as a ghost to wreak havoc

with his second marriage. I can imagine how pleased Coward was when he

thought of it. I can see him leaning back in his armchair, legs crossed,

silken dressing-gown a-swivel, inordinate cigarette-holder on duty in

languid fingers, while he indulged in a pseudo-bored little bout of

self-congratulation.

But in an era more morally inhibited than

today, he must have chafed at the realisation that he had better not

tell anybody. Good heavens, he couldn't start distracting people from

the war! So he didn't. And he went on not distracting them until he died

in 1973. Perhaps I should have kept his secret, but I think it was too

good to keep.

The same applies to

Kiss Me, Kate. Productions of

the musical often make intermittent play of a drop curtain purporting to

advertise The Taming of the Shrew,

because KMK is about a

company presenting this particular shot of Shakespeare.

PALPABLE UNCERTAINTY

So far, among the several productions

that I have seen, there have been two which have displayed what is

either a palpable uncertainty about Shakespeare's name or a

determination to go ahead anyway and see whether anybody notices. One

was presented by amateurs; the other was a West End production, on show

for months.

Either way, the result was a joke,

intentional or not – because the drop-curtain billboard credited the

book of the show to W.M. Shakespeare.

Wm, with only one capital letter and no

intervening full-stop, is short for William. W.M., with two full-stops

in place, is short for, say, William Makepeace, as in W.M. Thackeray.

Nothing to do with the Bard of Avon. Look out for it next time that

Kiss Me, Kate comes your way.

Anyway, as I was saying, if anybody feels

like continuing to plough what I think is a fascinating furrow, Noel

Coward, Arthur Mathews and the

Kiss Me, Kate scenery designers may prompt him to go rejoicing

further into the world of hidden humour. Who knows what may turn up?

John Slim

Protect us, please – we're going to the theatre

THE discovery that some West End theatres were using bouncers to confront the drunks who have been increasingly making nuisances of themselves was another landmark in the story of the decline in good sense and good manners to which Britain has become accustomed in recent years.

I am not at all sure when the rot started: like any other theatregoer, I feel as if I have been suffering the slings and arrows of outrageous sweet-wrappers for far too long. The same applies to the talkers – the under-instructed nuisances who are incapable of keeping their thoughts to themselves while the onstage action proceeds, and appear unaware that no one sitting within six seats in any direction is anxious to be privy to them.

But talking then moved on to shouting. Regular patrons discovered that the man accustomed to telling his television set exactly what he thinks of it in the privacy of his own home has no concept of keeping quiet in a darkened auditorium. He had to add his unenlightened contribution to the action.

INAPPROPRIATE MOMENTS

He arrived at about the same time as the hysterical whistlers and shriekers – who do, however, often manage to shut up during musicals, other than at the end of every number and especially at the curtain call; and there are the weirdly inexplicable gigglers who appear to be moved to loud laughter at inappropriate moments in serious plays.

And now, the onslaught of the uncivilized has led some theatre managements to take drastic action against those whose like have capped their previous exploits by turning up drunk and proceeding to fight, fondle and urinate, all in the public view.

The auditorium for Dirty Dancing has been described as a bear pit. Josef Brown, playing the male lead and supposed to make his entrance via the auditorium, had to start taking the more conventional route, via the wings, to ensure his safety from the depredations of louts who inflict on everybody else their inability to handle their drink.

AFFRONTED AUDIENCE

Even classic drama such as Terence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea has not escaped. Affronted audience members deployed the time-trusted Sssssh! when somebody called out during a particularly dramatic moment. All that happened was that the clown who had infuriated them responded, “Chill out, I'm only having a bit of fun.”

Certainly, it was a surprise when burly, bald-headed characters in dark glasses became noticeable newcomers to the scene – but their presence was both understandable and welcome. After all, if a visit to the theatre is going to degenerate to the extent that we need bodyguards, who else is there to rely upon in our increasingly frequent hours of need?

John Slim

Remembering the lines

IN the course of the average year, I probably spend far too much time sitting in a theatre's darkness, listening to what must be thousands of lines from about 130 scripts. The interesting thing is that I can remember virtually none of them.

This is no reflection on the quality of the writing, poor though this may sometimes be. It's more a reflection on me and my ever more discernible dive into dotage. Let's face it, I can't remember much of anything these days. Anything in the daily round that has the temerity to repeat itself is in with an excellent chance of coming as a total surprise. I haven't yet got to the stage of making new friends out of old friends on a daily basis, but I'm getting there.

Nevertheless, as far as an evening at the theatre is concerned, I can't help feeling that its ability to disappear beyond the grasp of my brain cell is not entirely down to me. I am sure that there really are not that many lines that actually stand on their hind legs and insist that they are worth remembering. So I must not chide myself too churlishly when I own up to being able to recall only three that I cherish.

ELDERBERRY WINE

There are nearly four, but the last line in Arsenic and Old Lace, another winner and I think only three words long, is eluding me. Not surprisingly, it's to do with elderberry wine. It's This is it or Here it is, but uncertainty reigns.

There is, however one line which I'm sure must be top of everybody's unforgettable list. It is A handbag! Never having seen the script, I don't know whether Oscar Wilde proffered it with an exclamation mark or a question mark. It doesn't matter, because this is the line that Dame Edith Evans delivered so decisively in a manner that indented for both adornments and went straight into the folklore of the stage.

It is the way she said it in The Importance of Being Earnest, rather than the line itself, that lingers in the memory – and inevitably, causes heart-searching among directors and actresses with every new production before the sensible ones realise that trying to say it differently just for the sake of doing so is a certain way of killing the humour.

So that's the first of my lines to treasure. The second relies on its words, rather than on the way they are spoken. Don't quibble, Sybil, in Noel Coward's Private Lives, is impossible to say, other than amusingly. Whoever delivers it, it has no option but to emerge virtually identically, with its humour ready-made to receive the delighted response from any audience.

On the other hand, Don't quibble, Gladys, which Terence Rattigan wrote in 1954, nearly a quarter of a century after the Coward version, does not have the same ring. In fact, it doesn't have a ring at all. This is presumably because Coward thought of the line and then named the character to fit it – or, having coincidentally chosen the name, was blessed with a blinding flash of inspiration when the moment came to write the line.

DERISORY COMPARISON

Rattigan, on the other hand, obviously knew of the Coward masterstroke and clearly could not create a Sybil for his cast list and for that line when he was writing Separate Tables. So he came up with Gladys, an extraordinarily ordinary name that yielded an extraordinarily ordinary result. He would have done better to do away with all thoughts of quibbling, rather than risk derisory comparison with the Master.

So I don't count Don't quibble, Gladys among my triumphant trio. It's a pallid, wasted moment, a distraction in an otherwise absorbing piece of theatre.

No, my third line to treasure is completely different and it is in a musical. Words, words, words! is spat out by Eliza Doolittle, the girl who is not a Cockney – but that's another story – in My Fair Lady. As with Don't quibble, Gladys, it's awash with déjà vu – this time, because it took Lerner and Loewe until 1964 to hand it to Eliza, although Tartuffe, the much-translated play that Molière wrote in 1664, had been sporting the line, or presumably something like it, for precisely 300 years. I caught up with it in 2006, in Miles Malleson's translation.

I don't know when Malleson, who died in 1969, aged 80, wrote his version – but I was further intrigued during the same production when Tartuffe regaled me with another of My Fair Lady's familiar lines, about the right and proper thing to do, which until then I knew only as part of Alfred P Doolittle's Little Bit of Luck number.

Clearly, one never knows what surprises a spot of theatrical archaeology may uncover. There's a book to be written somewhere, on the pleasures of plagiarism.

John Slim

Why doesn't Nanny bar

me from the theatre?

IT occurred to me without warning: why was I being allowed to sit among an excited bunch of massed mixed infants without Nanny Britain feeling my collar and looking unequivocally askance?

After all, this was a theatre – the Swan Theatre, Worcester, to be

precise – and theatres have increasingly come to be recognised by our

betters as places where people like me should not be allowed unless we

are appropriately certificated. CRB-checked is the official term. At

least, although I am at present still permitted to pass through the

foyer, I am not allowed backstage if the younger generation is present

in whatever quantity, even though backstage is normally adequately lit

and Nanny could readily see what I was up to.

Yet here I was, alone and unattended, intent on reviewing this year's

pantomime and being allowed to do so without check or hindrance – in the

dark, all by myself among several coachloads of school parties, with

just the occasional teacher on the end of a row.

Try as I may, I can't understand what prompted the sundry nonsenses

accompanying the Children Act. I don't know how many of the guiding

lights behind it can actually point to something rotten in the state of

theatre that made them decide it now has to be obligatory for

professional theatre companies and amateur groups alike to be strangled

by red tape and make sure that Authority is informed of everything they

are up to involving youngsters. In the case of youngsters in amateur

theatre, they are probably in the village hall, among adults they have

grown up with and friends with whom they went to school.

Far be it from me to put even more nonsensical ideas into the head of

Authority, but we are talking about brilliantly-lit stages and the

hinterland that accompanies them, where it isn't exactly necessary to

shine a torch. Why therefore has it not occurred to Authority to ask

itself what I am up to, sitting in the stalls in stygian gloom with

scores of children, no questions asked? Why was I not stopped at the

door and invited to come up with credentials? Why did Nanny not station

herself at the end of my row and frown forbiddingly?

As far as I can see, courtesy of the gloom aforementioned, I am far

better facilitated to be a menace to all concerned when I'm stationed in

the darkened stalls than I would be if I lurked in the wings or at the

door of a (suitably separated) backstage lavatory.

GRASSROOTS OFFICIALDOM

I shouldn't be saying this. After all the tentacles of too much

intrusion need only the merest hint that they may be missing something.

Out with the manacles! March me away!

And these nights, the ranks of grassroots officialdom are certainly big

enough to despatch me at the drop of a hat.

And why just me? How long will it be before nobody who is not

CRB-checked will even be allowed to watch a performance in which

children are involved or which has children in the audience? And in that

case, why stop at theatres? Cinemas are even darker and therefore more

cosily co-operative than theatres. I'm sure the bureaucrats and the

box-tickers, once started, will be able to arrange for every member of

every audience to be frisked beforehand. After all, there are enough of

them.

At the Swan, for instance, listed euphemistically under Credits, were

the names of the senior matron, the senior chaperone adviser, eight more

matrons and eight more chaperones – a powerful platoon substantial

enough to see me off the premises, no questions asked.

I was interested to observe that one of the chaperones was called Lusted. That was something I didn't do all night. Honest, officer.

John Slim

A moleskin marathon

SOMEBODY, possibly me, reminds us from time

to time that all the world's a stage. So bear with me while I tell you

the story of its longest-running farce. It was revealed in the national

press in 1997 and I have treasured it ever since. I hope it will give

sustenance and encouragement to anyone now embarking on The Great

Christmas Present Hunt.

It's the story of a Christmas present that was

unwanted in 1965, and of the two American brothers-in-law who came to

realise that it would solve their mutual annual gift-buying problem for

ever – or at least, in alternate years.

Not to put too fine a point on it, it's the story of

the moleskin trousers that Larry Kunkel's mother bought him when he was

a student, in 1965. He was unimpressed, but he kept them,

virtually unused, in his wardrobe for five years before deciding to send

them to his brother-in-law Roy Colette, in

Roy was not impressed either, and returned the

trousers to Larry in Illinois the following year, complaining that they

froze solid in cold weather – which was part of the reason Larry had

given them to him in the first place.

In 1972, Larry sent them back again and the tradition

became established – but because neither man wanted to have them

returned they both became adept at making it as difficult as possible

for the recipient actually to get at the trousers.

The first significant wrapping came when Roy returned

them in a long tube. Larry sent them back 12 months later in an old

insulated unit.

BUCKET OF CONCRETE

The following year, Roy despatched them in a

10-gallon bucket of concrete. The Heavy Packaging Era was born.

It took two years for Larry to extricate the

trousers, to enable him to return them inside a specially constructed

240lb steel ashtray.

Roy used a 100-ton hydraulic press to release them

before he returned them the following year in a 600lb bomb-proof safe.

This was not only locked but also welded shut.

Twelve months later, Larry obtained an old AMC

Gremlin car, put the trousers in the glove compartment and had the car

crushed into a 3ft cube, round which he tied a red bow. The finishing

touch was always important.

Undaunted, Roy returned them in a 6ft-high

‘indestructible' Goodyear tyre filled with concrete and weighing more

than 3,000lb.

The following years saw the packaging take the form

of various types of motor vehicle. One of them was a station wagon

packed with numerous electric motors, only one of which contained the

trousers.

There was the year when Larry encased the trousers in

a concrete-filled, steel-coated rocket ship, 15ft high and weighing

about 10,000lb, which was delivered to Roy's front yard – only to return

in 4ft-square cube, made from special concrete used on airport runways.

After Roy had received a cement wagon painted like a

space module and filled with 20,000lb of concrete, he decided on the

ultimate return for Christmas 1991. It took the form of encasing the now

badly-worn trousers in a 10,000lb glass iceberg.

Alas, they were burnt in the preparation, so all

Larry received was the ashes. He treated them as they deserved and

preserved them in a brass urn on his mantelpiece.

This was farce on an almost unimaginable scale – a

slow, majestic process of infinite inevitability that rose far above the

mere opening and shutting of doors and the dropping of non-moleskin

trousers. It lasted from 1970 to 1991, when it officially came of age

and had to be forcibly finished after plumbing the depths of superhuman

determination.

Heaven knows where Roy and Larry are now and I would

not dream of wishing them harm – but if they have both perchance risen

to higher things in the last 18 years I hope that there are two

tombstones somewhere, recording their contribution to the annals of

glorious lunacy to which many aspire but which few attain – and never,

surely, on a scale so implacably epic.

If either monument refers to an innovative evangelist

of the hilariously surreal, I hope that a passing pilgrim tries to read

it aloud. He might possibly corpse.

John Slim

English as she is spoke

WATCHING a young group in a studio production, I was

impressed to see the quality that shone out. As long as this kind of

talent keeps emerging, amateur theatre will have nothing to worry about.

But with the delight came the reservations –

and I'm afraid they take me back to my long-held misgivings about what

we're doing to this wonderful language of ours. Several times, it was

impossible to avoid the realisation that these young people were falling

into the same sorts of traps that ensnare actors of all ages, all over

the country.

So we heard

mischievous spoken as

if it rhymed with devious,

and noblesse oblige

had clearly been fitted with an unexpected final acute accent.

Sedentary came up

with the stress on its second syllable – as indeed did

inventory, which

actually has nothing whatever to do with

invent. Communal

constantly suffers the same misfortune. Its links

are with common,

not communion.

Meanwhile, our old friend

drawing is

almost inevitably provided with an R in its middle.

This is but the tip of the iceberg of

mispronunciation with which theatre, both amateur and professional, is

bedevilled.

Television is by no means

immune. I am recovering from the dismay with which I greeted my

discovery that, in defiance of what I was taught,

proven no longer

rhymes with woven

except in

From time to time, we

hear that restaurateur

has been burdened with an N

that turns its rat into a rant, which is what Gordon Ramsey, who is not

entirely unknown for his rants, always does.

Then there is

controversy, in

constant danger of being given an accentuated second syllable. And

somebody, somewhere, ought to make it clear that

says rhymes with Des

and Les, not with days

and lays.

Less frequent, and

therefore still more of a shock to the system when it jumps up and bites

me, is redolent,

when pronounced with stress on its middle

syllable. It is presumably a word that has never come the way of the

guilty party in real life, nor, indeed, of 90 per cent of the average

audience – which is precisely why it merits some kind of pre-production

enquiry into what it should sound like when it receives the rare chance

of an airing.

An actor's responsibilities don't end with learning

his lines. He must also learn to speak them.

John Slim

AMONG the fairly common

expressions that Americans can't say are

got to and

going to. And we British, being so

assiduously accommodating in our relations with the US of A, even when

it comes to using our own language, have adopted the transatlantic

versions into our own everyday use. What a helpful lot we are!

Even our radio and television

presenters, for whom words are their job, join almost every interviewee,

of whatever status, in saying gotta

and gonna.

They clearly understand, speaking speechwise, that

our status is Yankee poodle.

Whenever I have seen

Seven Brides for Seven Brothers,

with British theatre groups doing their best to be

American while they sing We gotta make it

through the winter, it is obvious that

they have no

difficulty with gotta.

By now, it comes naturally.

On the other hand,

intriguingly, winter,

particularly when sung, clearly tends to be too

much for any hopes they may have of appearing to be a real live nephew

of their pretend Uncle Sam.

They need to remember that no American has yet mastered the fairly straightforward pronunciation of the N-T sound. This is why his every winter is a winner.

Another aberration results in his government's

readiness to use rocket-propelled missals, whether or not it is fighting

a holy war, to be made apparent by its spokesmen – and the British on

stage do try hard to remember to show themselves to be aware of these

and other idiosyncrasies.

But not when they're singing.

Let's get back to N-T.

I have seen wanted prove just as problematical as winter, once it is part of a libretto. In Copacabana, I saw the leading lady, along with the rest of the company, make a believable fist of the job of speaking American. But then she had to sing Man Wanted, with its title phrase recurring repeatedly – and she reverted immediately to being a charming English rose. There was not a hint of the mairn wannied that should have been as much a part of her alter ego as a bespoke bra.

APPLE PIE AND MOTHERHOOD

I had been suspending my

disbelief for the entire show, in order to view her as being roughly as

American as apple pie and motherhood seem widely supposed to be – but

suddenly she became incontrovertibly English and I had to suspend the

suspension, especially as she was not offering an American version of

man any more

than she was of wanted..

A-N,

like N-T,

is a little two-letter pairing that utterly

defeats the greatest nation on the planet. This is why, when the

pairings combine, they could be lethal. The transatlantic cousins are no

more reliable in saying can

than man.

They say cairn,

meaning can,

and cairn,

meaning can't.

Fortunately, despite their

self-imposed problems, Americans do seem to understand each other most

of the time. I hope that this will be confirmed when we learn that their

president – any president – with his finger hovering over the nuclear

button, turns to his advisers and says,

“Cairn I?” and his advisers say,

“Mr Presiden', You cairn”

All the same, I shall feel safer if they stick to

their rocket-propelled missals.

John Slim

Are stage fatheads under threat?

IT had never occurred to me before, but

suddenly I realise that it's pretty difficult to play a fatheaded

Englishman and make him camp as well.

The revelation occurred when I was

watching a production of Anything Goes, in which Sir Evelyn, the archetypal chinless wonder,

was also presented as being what I understand is technically termed on

the other bus. And the two characteristics just don't mix.

Stage fatheads are precious. They are the

What-what-what burblers at whom the world cannot help laughing. They are

put upon by stronger-minded citizens. In any crisis, they are the

victims. They are hapless but eternally hopeful.

In contrast, a camp character can be

portrayed as strong and decisive, though ‘different.' He can dominate a

conversation and be – intentionally – very funny, where your latterday

Bertie Wooster is amusing only in suffering the bludgeonings of fate and

in his reaction to them.

If you're camp, it seems to me from what

I've observed in real life, you're also in with as much of a chance as

most people of being somewhat spiteful – but this is a

trait that would sit uneasily

on a prize fathead who habitually has not a naughty bone in his body.

I suppose that in saying the two cannot

be combined I was perhaps basing my judgment on my single sighting of an

attempt to make it happen. Perhaps, somehow, an unlikely merger could be

achieved, but it would demand a sizeable suspension of disbelief on the

part of an audience conditioned in daily life to expect to be confronted

by the characteristics of only one or the other in any one person at any

one time.

Were I ever bold enough to be directing a

production involving a chump with a chin shortage, I would have to

insist that he was played straight – even though I know I would be

tempted by sheer curiosity to let him camp it up as well, just to see

whether the hardly-credible can actually be achieved.

John Slim

When a cow has wings to worry about

HOW do you help a cow to traverse a spiral staircase?

Answer: you don't – especially if it's for pantomime,

with a cow consisting of two 14-year-olds, and even more especially if

there's one of our latterday theatre chaperones on beady-eyed watch.

The problem facing members of

BMOS Youtheatre in their production of Jack

and the Beanstalk was that if you exit

stage right at

Birmingham's Old Rep it is necessary to go down about a dozen steps to

take you either to the stage door or under the stage, where you walk the

width of the stage until you reach the sharp and steep spiral staircase

that takes you up into the wings, stage left – where there is not room

to swing the proverbial cat, let alone manoeuvre a panto cow.

It's not the easiest of places to practise

pantomime herdsmanship – but the supervisor of Daisy the Cow would not

let her be led off stage left because once they got there they could not

turn round in readiness for her next entrance. This was why the wicked

Fleshcreep, having got possession of Daisy and being required to get her

offstage, had to defy the rules of pantomime which say that Evil must

not cross the invisible line centre-stage which separates it from the

domain of the Good Fairy, stage- right.

In another scene, for the same reason involving

a confrontation with the spiral staircase, he had to go stage-right

again to lead Daisy back on. And there was no prospect of outwitting the

chaperones: there was one on the stairs going down from the stage,

another underneath the stage and one more on watch in each of the wings.

Fortunately for BMOS Youtheatre, what director

Alan Hackett says would have been “quite a mammoth job” of finding

enough police-checked chaperones for the run of the production was eased

because every member of the committee had been checked – but one had to

be hired for the Friday and Saturday nights at a cost of £80.

And

before the curtain rose on the first night, authorities in

It is to Youtheatre's credit that the audiences

who cheered the youngsters on did not suspect half of the hurdles that

had been placed in their way.

John Slim

Youngsters are the pawns in Nanny's nonsense game - Features

Officer, my car's gone. Again

PARKING paranoia has been building within me for many

years, but it has taken

This history-filled theatre in

I was barred from my longstanding parking haven.

A kindly citizen eventually sorted me out and I crossed the theatre threshold barely in time for kick-off but nevertheless in plenty of time to be separated from £2 for raffle tickets in the foyer.

ONGOING EARTHWORKS

My next and most recent visit was easier because I

knew I must not be lured by the lower-level ramp – still closed, quite

possibly for ever, as far as I can see, because of New Street Station's

ongoing earthworks. There was a queue of six cars at the top of the

upper-level ramp. The helpful woman driver at its head revealed that the

ticket machine had run out of tickets but somebody was trying to find

some. Fifteen minutes later, I was in part consoled because the very

first parking spot beyond the barrier was available, which meant that

the only fly now in the ointment was the need to walk back down the ramp

and round its blind bend in the presence of two-way traffic.

Again, I drove to the exit machine, tried the ticket again, failed again, and then pressed the SOS button and confessed all to the unseen voice that was coming to my rescue. Two minutes later, as if by magic, the barrier lifted.

These two visits to the Old Rep were the crowning in

uncertain glory of my relationship with car parks and car parking, which

started about 20 years ago when my wife and I were visiting a daughter

who lived in an area of London where the streets were laid out in a grid

system and nose-to-tail parking was the order of the day. Having left my

car, of necessity, a long way from where she lived, I returned the next

morning and it was not there.

Well, it was – but I was looking for it two streets

too soon, as the local police station rang to tell me some time after I

had reported it missing. The constabulary also kindly advised me to move

it as soon as possible, without saying why. When I got back to the car,

it was the only one in the street, which now had hundreds of yards of

traffic cones on both sides. A tennis tournament was due at Queen's

Club.

Then there was the time I parked in the multi-storey

at

At

I then reported my misfortune to the company

responsible for my car's tracking device. Don't worry, Sir: it will turn

up.

CAR-FREE DRIVE

I didn't have time to worry.

I also involved British Rail's police in a car park

crisis, this time at Birmingham International. Because of my

undistinguished record in these matters, I had made a point, before

catching a morning train to

Well, yes, it was there after all – but it was

alongside the third lamp standard from the other end.

I do not have a good record as a putative parker. I really did not need the Old Rep to confirm this for me. I can only hope that New Street Station is returned as rapidly as possible to the sort of parking procedures that even I can cope with.

John Slim

A trick of the light

I

SOMETIMES think that stage directors are not aware of the box of tricks

they are opening when they begin playing with the lighting.

Light is not an affable, easy-going element that is happy to be

underestimated, let alone ignored altogether. When it's on your side, it

can be a magical thing, beguiling the senses and firing the imagination.

I shall never forget a superb amateur production of

Dr Faustus at

But lighting has to be controlled. Take your eye off it, let it off the

leash without due consideration, and the results can be amusing,

surprising or just plain uncomfortable. I have seen a couple of

productions in which the lighting plot came into this last category. One

was Grease, in which, for

reasons unknown, the car's headlamps were allowed to blaze unwaveringly

into the audience. It was not pleasant.

Far too often, I have sat in on musicals where there has been careless

lighting in the wings, allowing the shadows of waiting cast members to

give us a four-minute warning of their impending arrival – even if the

players had not already shown themselves by standing far too close to

the action before their turn had come.

I remember one show that had a centrally-placed glass door upstage.

Nobody ever actually used the door, but there was an unaccountable light

behind it that enabled everyone to see the pedestrian traffic as it went

by behind it.

Infra-red – or is it ultra-violet? – lighting is a law unto itself. One

production had a line-up of three angelic young ladies dressed

head-to-toe in white. On the night I was there, the lights came on and

they were suddenly parading in their underpinnings.

I am never comfortable when I am required to believe that a scene is

being played in total darkness when everything is as plain as a

pikestaff in the token gloaming. This sort of scene can usually be

relied upon to involve a surprise assault or a gunshot, and it's hard to

accept that the victim is the only person in the theatre who can't see

what's coming to him.

Having said that, I have noted one or two occasions recently when darkness has really been dark – so perhaps we are beginning to nibble into what is a pretty stupid convention. All right, I can imagine that Health and Safety will not rest easy in its bed at the thought that thespians everywhere have been exposing themselves to the unimaginable dangers of being onstage in the dark – but it surely cannot be all that difficult for a director to drill into the troops an awareness of where the furniture is.

Anyway, I'm living in hope of a few more touches of realism.

Talking of darkness, and admittedly it wasn't completely dark although

it was a near-miss, I have never forgotten an

Arsenic and Old Lace that I

saw more than half a century ago. Nothing was happening at all. Nobody

was there. There wasn't a

sound. Then suddenly, stage left, a sashcord window was lifted open with

a resounding thump.

On reflection, it should have roused the household, but I didn't think

of that at the time. Nor, I am sure, did anybody else. What it did do

was make the audience give a concerted gasp, then settle back in one of

those wonderful, pleasurable, spine-tingling panics while a couple of

intruders climbed through the window, accompanied by an exaggerated

leavening of nervous laughter.

This was a moment when light was harnessed and disciplined and put to

work for the general enjoyment. It was excellent and I'm sure I was not

the only audience member who went home and boasted that he didn't have a

heart attack.

Light does have to be brought to heel. It's not going to do what you

want it to do without practice and prompting. And it's no good assuming

that because it's always behaved itself for you it can be trusted to go

on doing so.

For instance, I finally caught up with

The Mousetrap when it had been

running for half a century. And what do I remember most about it? It was

the moment when the butler – it must have been the butler, surely – went

to the light switch. I can't remember now whether it was to turn the

light on or off – but what I do remember was that the light declined to

respond to his practised touch. And this, after 50 years.

Good lord, I thought, there's hope for amateurs everywhere.

John Slim

Theatre Visit

How many times does man repeat

An awesome process, filled with

doubt,

When aiming for his theatre seat,

To enjoy an evening out?

Can the social whirl produce

Refined revulsion, quite

exquisite,

To match the civilized abuse

Contained in any theatre visit?

No helpful course provides

instruction

That guides a fellow when he

sees,

Without a formal introduction,

That he must climb a row of

knees.

Edging sideways while repeating

Apologies with dazzled eyes,

Past pre-ordained dress-circle

seating,

Paved with mini-skirted thighs.

Should their owners choose to

stand,

He cannot fail to be impressed,

In the

Tête à tête

with vest-top chest.

Sometimes knees are too

arthritic,

Locked and painful, cannot move.

Let me past, 'cos I'm the critic,

With prejudice I need to prove.

Can the problem be much worse,

If I have a gangway seat?

Certainly, it's in reverse,

With me the yo-yo on my feet.

Indeed, a gangway seat is worse,

If this is what harsh Fate

decrees.

Cough conceals the muffled curse,

Swapping bumps with unknown

knees.

Greet the next one, smile

disarming,

Sotto voce

swear less sweet.

She's leaning forward, most

alarming.

Face-to-bust, I overheat.

And still they come, the

trampling tribe.

Some say

Thanks and some say

Sorry.

Some adopt an ill-judged jibe –

Hunters all who've caught their

quarry.

But now at last a hush descends,

Expectant for the main

attraction.

With luck, the knee-knock

nuisance ends;

Yields to less absorbing action.

I'm bruised in body, mind and

soul.

Emotions jarred, I claim my seat.

I've elbowed to my cushioned

goal,

Refusing to accept defeat.

Mankind can never hope to know

Why theatres think they need a show.

John Slim

Some really special cell padding

THOSE bright eyes at Highbury Theatre Centre, Sutton

Coldfield, don't miss much. Mind you, they would have been hard-pressed

to miss the newsletter that has emerged from the National Operatic &

Dramatic Association (NODA). It's the longest email I have ever seen.

There are yards of it.

And it's largely gobbledegook. This is

obviously not the fault of the people from whom it appears to have

emanated, variously referred to among the digitally dispiriting nonsense

as

mailto:stephanie@noda.org.uk?subject=3DCont=

ributuion%20to%20newsletter> and

http://mailmanager.johngood.com/t/r/o/dufg/ykukehkj/o.gif.

No simple human brain could have

made this up. I am sure that when it left them it was a helpful note

that consisted merely of the gems of information that are now buried in

the cyberspatial equivalent of a rubbish dump – and it may indeed have

tied itself in knots only while seeking to leave Highbury and bring me

bemusement on a scale I have rarely encountered.

I realise that every now and then

computers feel compelled to remind us that they are firmly in charge –

but some computers clearly don't know when to stop.

This particular one started

by saying FLAVOROO-NONE-0000-0000-000000000000 before

vouchsafing: “Received from [172.23.270.139](helo=anti-virus01-10) by

eback01.blueyonder.co.uk withsmtp (Exim 4.52) id 1Mw 1Wc-0006v4-ST.”

If that couldn't whet your

appetite, what will?

But then you may begin to suspect

that you are on the trail of something useful. Or will you?

“The

A little later, we find something called

3DINCRFEDIMAINTABLE, which leads us gently to CELLPADDING=3D2 and so on

to 3D PADDING-BOTTOM, PADDING-LEFT and PADDING-RIGHT.

If we persevere, we discover that

NODA is trying to tell us something about its new regional magazines,

working with children in theatre, the Really Useful Group celebrating

its 40th anniversary by releasing Jesus Christ Superstar for

amateurs – and a free subscription to the NODA newsletter. Now there's

an offer you can't refuse. . .

On the other hand: “If you

do not wish to receive this email in the future please click

<http=://mailmanager.johngood.com/t/r/u/hrlhit/ykukehkj/>”

Johngood will remain unmailed. I wouldn't miss it for

the world. It's incrfedimaintable. Meanwhile, I'll indent for some more

cell padding.

John Slim

Sounds unlikely

FOR me, the Geordie accent is the most difficult

in Britain. Not that I'm any good at accents anyway, but while I can

sort of go nasal enough for 15 seconds of far-from-passable Scouse, the

sing-song tones that bestride the Tyne leave me totally unable to make

or achieve a good impression.

So I have every sympathy, in a sense, for theatre people, amateur and

professional, who are called upon to evoke the sounds of my native

Birmingham and who almost invariably make an utter hash of it. Where I

do not sympathise is when their often excruciating failure is part of

yet another of those habitual efforts to mock the

All right, I'm biased, but nobody chooses either his birthplace or the

speech patterns it gives him, and the Birmingham accent tends to be the

nation's whipping-boy. It's odd that seemingly everyone thinks it's a

doddle to deride but then falls down abysmally in actually seeking to

pile on the laughter.

BRUMMY ACCENT

The fact is that you don't find a genuine-sounding Brummy accent other

than from genuine Brummy natives, such as Jasper Carrott and Julie

Walters and the anonymous thousands who teem in Birmingham's Bull Ring.

Come-lately nonsense, by the way, has decreed that the Bull Ring, a

marketplace that has been at the heart of the city's life for centuries,

is now officially Bullring. No

The, no space between the two words, no sense of history and no

intelligence, just a quick hurray for the City Fathers. But I digress.

I'm glad that Brumspeak is not a frequently-favoured vehicle among

playwrights, because it's virtually inevitable that it emerges as a

caricature. Lots of whine – too much – and loads of untamed vowels are a

cringe-making embarrassment for anyone whose daily round is full of the

genuine article.

I learned from my local television news one night that we were drawing

towards the close of National Brumspeak Day, when everybody was supposed

to have become a pretend Brummie. I was glad that it had not impinged on

my awareness. It's bad enough to have to sit in a comfortable theatre

seat and put up with desperately-flailing professionals making a mess of

the accent: heaven forbid that I should be assailed in the street on all

sides by jolly amateurs.

There are certain basic rules to Brumspeak, particularly with the

vowels. Its E, for example,

emerges as what can best be described as the French

oeil, as in

throeil coins in the fountain.

A Brummie doesn't say I,

except when he means A; and

when he means I, he says

Oi. The result is sentences

like, Oi'll wite at the soid gite.

If you hear a Brummie say, Oi,

it is important to understand that he is not trying rather rudely to

attract your attention, he is referring to himself. I am

Oi and you are

yow. This is because his

O is pronounced

Ow, except in

go, which is

goo.

THE PLOT THICKENS

At this point, the plot thickens – because although he says

goo (because he can't say

go), he can't say

you, which is either

yo or

yow. This might appear to be

pushing logical lapses to the point of perversity – but he is not being

perverse. Unless it is for the purpose of pseudo-studious witterings

like these, he does not give a thought to how he speaks, any more than

do the Cornishman, the Yorkshireman, the Scots and the Irish who leave

Professor Higgins close to sneers with every performance of

My Fair Lady.

But the Brummie's pronunciation is merely the iceberg-tip of his own

special language. His past tense of

know is

knowd, pronounced to rhyme

with cowed. If your

God-fearing Brummie says, Oi sin,

he is not embarking upon a public confession, just pointing out that

he saw something.

And he lives in the present. When he says,

Oi cum home, he is not

referring to a daily habit but to his recent return to the bosom of his

family.

Sadly, Brumspeak is not addressed in drama schools. It's a big gap in

theatre studies and it means that the attuned ear is always going to

suffer when plays or musicals purport to present a son or daughter of

Until Birmingham's playwrights start flooding the market with home-based

material, it is unlikely that the situation will ever change. Meanwhile,

in Brum, you'll find it talked but not taught. Everywhere else, it's

mocked and mangled – but it's we genuine articles who are laughing.

When we're not cringing, of course.

John Slim

Witter

isn't twitter

ODD, isn't it? After more than half a century scribbling my witterings for the printed newspaper page, I am suddenly embarking on this increasingly popular business of scribbling for cyberspace. Press a button, and they're gone. Now you see them, now you don't.

Even more unlikely, it's a change I chose for myself – but only, I add in self-defence, because the current upheaval at the Birmingham Post and the Birmingham Mail means that there is no longer any room for unpredictable newsprint prose on the state of amateur theatre, which is a world I have been exploring for a quarter of a century, entirely by accident and without having given a thought to the subject for more than 50 years beforehand.

It was in 1984 that the man whom the Post and Mail had taken on to cover the amateur stage decided to leave. That was when an anxious features editor with a space to fill asked me if I would mind looking after it this week. This week became 25 years. I hit retirement and then some, but went on wittering – and suddenly the Post and Mail can't take it any more, which is entirely understandable.

Suddenly, therefore, it's me for the ether. Keyboards a-swivel!

I ought to make it clear right away that although I witter, I do not twitter. I have not managed to get my brain cell round the idea that the world might like to know that I am twittering with one hand while eating an apple that I am holding in the other.

EMPTY MILK BOTTLES

I am fairly convinced that only I am interested in the fact that I like to put two empty milk bottles in a bowl of water, watch them gradually fill up, and see which one sinks first.; or, for that matter, turn both taps on full until the bowl overflows, then switch them off and watch the water continue spilling out – while I wonder where it's been all this time: it can't have been in the bowl, because there's no room for it.

Like my speculations on the size of a greenfly's kidneys, these are considerations of quite remarkable inconsequence. They are the sort of things that keep my brain cell super-active and they are probably important enough for twitter, but a fellow should be allowed his sense of shame, so I'm not saying a word. Please ignore these last three paragraphs.

So cyberspace and I are unlikely bedfellows. I'm the one who responds to the sounds of a newspaper being read – the homely, comforting, crinkling noise that shares an armchair and does not require me to perch in front of an implacable screen.

Nevertheless, in a matter of weeks, cyberspace has claimed me twice – for www.behindthearras.com and for the national magazine of the National Operatic & Dramatic Association (NODA), which I have been editing since 1997. Suddenly, NODA is appalled at the cost of publishing its assorted outpourings, which include nearly a dozen regional magazines as well as the national one – so NODA, too, is launching me into the world of getitonline in time for Christmas.

If I meet myself out there, I shall hardly know what to say.

John Slim