Falling for the joy of Gyles

AS a postscript to my recent

communique regarding a date in Taunton for my wife and me to sit in on

the appearance of Gyles Brandreth at the Brewhouse theatre, I can now

report that I duly kept the tryst, courtesy of daughter Beverly and

son-in-law Nick – and that the erstwhile evangelist of jumpers provided

a quite superb evening of thoughts, observations and reminiscences –

every one of them beautifully honed to provide a veritable harvest of

comedy.

From the beginning, he commanded the stage, exuding a sort of unfailing but surprised happiness and striding forcefully from one side to the other, punching the space before him as he went.

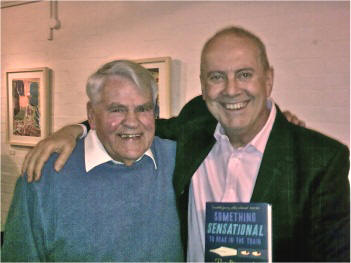

Aging groupie John Slim (left) with Gyles Brandreth

Early

on, he started exchanging pleasantries with a young lady called Alison,

sitting in the front row, stage left. She became an intermittent feature

of the evening, to everyone else's delight and presumably her own.

On arriving at the theatre, I had got an attendant to

agree to go backstage with a note accompanying the latest of my eight

books of original limericks – Short and Sweet – A thousand virtuous

limericks – so that the man of the moment, who had written the

foreword to the first in the series, could see the oeuvre's

latest offering at some point when he did not have the more pressing

obligation of entertaining several hundred expectant citizens.

The result, right at the end of a riotous two

hours, was that I got an honourable mention from the stage, accompanied

by a reference to the Big Birthday that was to follow four days later.

Then, after he had taken his bow and disappeared into the darkness stage

left, we found him in the foyer, where he hailed me with a huge cry of

“John!” that was the cue for an instant bear-hug.

I was carrying Something Sensational. to Read in

the Train, the diary-based autobiography that takes him from the age

of 11 in 1959 to 1999 and finds him giving the world a privileged peek

at his multifarious diversions and what makes him tick so irresistbly.

He promptly inscribed the title page with kindly words in impeccably

extravagant handwriting and dated it with my birthday.

This was a joyous encounter, but presumably our last

– and that's sad. On the other hand, he will be at the Palace Theatre,

Redditch, on Sunday, February 13. . .

Is there a law that bars an 80-year-old from becoming

a groupie?

John Slim

Toast, anybody?

I LIKE Jamie. You know who I mean. Like

Delia, he appears to be galloping through his television career with

minimal recourse to a surname.

He's the boy-next-door-cum-inspirational-chef. His

latest book inspired me to try to follow in his footsteps. In the

kitchen, not on television. Once.

And now I learn that I am not alone in failing to

meet the Oliver expectations. Not that he would have had any

expectations if he had actually met me, of course. But our paths have

never crossed, so it falls to me to tell him that he is not the first

Oliver to have hoped in vain for more.

I am not a cook. I am a cheese-on-toast boiled egg

man. I have even demonstrated my inability to cope with a cafetière – by

loading the coffee grains, not into the pot but into the plunger tray.

The culinary arts have somehow passed me by – though I am a sucker for

television programmes in which the experts work their magic.

Inevitably, I watched Jamie's 30-Minute Meals,

based on his book of the same name. There he was, crash-bang-walloping

ingredients together with his customary boyish abandon in pursuit of the

result that was his target, and somehow finding time to chat without

pause in the likeable lisp that is his trademark.

More in hope than optimism, despite the ease with

which the affable expert had whizzed through the business of creating

wondrous feasts, I acquired the book. Alas, I was not at all surprised

that it failed to circumvent my ingrained culinary cowardice and my

refusal to believe that it could miraculously enable me to create the

wonders it contained.

And it appears, sadly, that I am not his only lost

cause. It seems that even cooks of experience have been finding that a

30-minute meal can take 1½ hours to produce – the reason being that

by the time the average pioneer has assembled all the ingredients that

Jamie has decreed – even if they actually happen to be readily available

– a substantial chunk of those magic 30 minutes has been eaten up.

Moreover, he who plans to follow the Jamie road to

magic meals also needs the accoutrements. Forty-nine of them. They're

listed on page 21.

The first recipe is for broccoli orecchiette,

courgette & bocconcini salad and prosciutto & melon salad. Twenty-one

specified ingredients. Don't despair, just get on with it. I wish!

Even if I had ever confronted my cooker with intent,

I would have turned pale at the edges – aware in my ineptitude of a

recurring vision of a blur of blond affability steaming through the

successive stages of a challenge that has had me tagged on the instant

as a non-starter.

I fear that the evangelical Jamie, who has been

rightly praised for his efforts in spreading the gospel of healthy food

and how to tackle it, is several light years ahead of me in all

considerations culinary.

Now then, who's for toast?

John Slim

Don't put your bottom

on the stage, Mrs Worthington

IN relation to something over a quarter of a

century in which I have been chasing amateur thespians across their

boards, I have not known Walsall's Grange Players very long. That is to

say, I have known of them for

25 years, but it is only in the comparatively recent past that I have

begun crossing the threshold of the Grange Playhouse with any degree of

regularity, to find them at first hand.

What follows, therefore, is a belated display of

delight at what I have found inside the single-storey, unpretentious,

brick-built building clad in corrugated metal and fronted by an

unexpectedly spacious and intermittently muddy car park. An age ago, it

used to be an exclusive tennis club, and then during the Second World

War it became the headquarters for the local volunteers of the National

Fire Service.

Also during the war, the formidable Kathleen Bullock

formed the 14th Rangers Company at a Walsall church,

with drama an important item on its calendar – an arrangement which

worked well until a vicar had the temerity to insist that he would vet

any play before it was presented. Clearly unimpressed, Kathleen then

launched the peripatetic Studio Players, who laboured for four years in

the wake of the NFS to reconstruct the interior of what is now the

Grange Playhouse – where they introduced themselves as the Grange

Players in 1951.

They have gone from strength to strength, despite

losing the dressing-room side of their theatre, along with irreplaceable

costumes and props, in an arson attack in 1980.

What I have discovered in their home is a joy of cosy

intimacy, where the interval finds the wooden-floored foyer – which is

also the box office and the bar – consistently full of playgoers who are

mainly middle-aged and all seeming to know each other, standing

shoulder-to-shoulder, sip-for-sip, because there is not enough room to

put in more tables without cutting down on the gate receipts.

Meanwhiile, away from the convivial uproar, the

interval turns the auditorium into a restful haven in which discerning

patrons are able to remain in their seats and have cups of tea served on

trays by the ever-pleasant front-of-house volunteers.

It is an auditorium with seating for 104. That is to

say, there is not a lot of it – and it is in high demand. The Grange

Players have a record of going through season after season with

virtually full houses and waiting lists for the frustrated.

Last year, for example, there were 129 of them

champing at the bit while they hoped to get in to see Gym and Tonic,

142 similarly on the outside looking in for Carrie's War, and

a remarkable 237 who had planned to applaud The Darling Buds of

May. This season, when Run for Your Wife opened on January

13, the number of prospective patrons hoping for tickets was just three

short of what would have been another full house.

In 1982, the Players counted themselves lucky when,

on the night before the Sunday dress rehearsal of The Heiress,

thieves got in and stole the sound equipment and lighting decks. Lucky?

Well, yes: the intruders decided not to bother with borrowed props

including valuable vases and a trinkets box – and a fireplace worth

£700. They overlooked a potential haul worth £8,000.

The auditorium is a pleasing little space. There is

little danger that any patrons will get lost inside, even though the

front row is Row F – but the Players nevertheless take no chances. Their

commendable system of ticketing means that every ticket, in addition to

displaying the seat number, helpfully makes clear whether it will be

found on the left or the right of the central gangway – and this, in my

experience, is pretty unusual in the world of amateur theatre.

The gangway is in fact a staircase flanked on each

side by half-rows, for the most part consisting of eight seats, and its

successive steps are thoughtfully illuminated.

The dark red walls sport bright little wall-lights in clear glass tubes.

Apart from its tea trays and Row F (for Front), the

Grange has an occasional idiosyncrasy that intrigues the uninitiated. It

puzzled me when I went to see Brontë. At one point, the

performers were joined by off-stage sounds caused by a high wind

rattling the vents on the extraction fan in the auditorium roof – an

experience new to me but familiar to the Players, who say they have no

control over it. The rain is also liable to rattle on the roof.

But it doesn't matter: it augments the audience's

feeling of being cosily all-in-this-together-and-we-shall-see-it-through

as it huddles up and concentrates on the action.

And before Brontë began, there was another

pointer to the sort of thing that makes the Grange rather special. Those

auditorium steps lead down towards what is a distinctly low-slung stage

with a gap in front of it that gives just about enough room for patrons

to make their way along the front row.

On the first night of Brontë, a woman had

paused in her pilgrimage to her seat in order to have a chat with

front-row friends sitting by the gangway – and had clearly made herself

comfortable while she sat on the lip of the stage. It was the only time

I have seen an audience cleared from a stage – be it never so politely –

before the start of a performance.

But this is the Grange, where Run for Your Wife

– running being the order of the day until January 22 – is the

Players' 281st production. It's the Grange. It's

different!

John Slim

It's bus time with Brandreth

I LIKE coincidences. They remind me that

Somebody Up There has a sense of humour. They allow me to say, “Well,

would you believe it!” – and I do enjoy asking questions that don't have

a question mark.

It is about 40 years since I met Gyles Brandreth for an interview at his London home. I remember that the resultant article was accompanied by a photograph of him doing something silly with a pillar box. Most of all, though, I remember his relentless amiability, his supercharged enjoyment of the world around him – even me.

He told me that he had written the world's shortest

poem, Ode to My Goldfish. It went, “O, wet pet.” And I was able

to respond by telling him that I had written the world's longest poem to

consist of a single sentence, taking the form of a question and

beginning, “Have you heard how Cuthbert Hatch.. . .”

It was a one-sentence question containing 320 words,

of which I recited to him as many as I could remember. What with that,

and with the Brandreth wet pet, we got on like a house on fire. I

subsequently expanded my single-sentence opus to 336 words and turned it

back on itself so that it began all over again and therefore had no room

for the question mark – nor even a Would-you-believe-it! exclamation

mark.

Since then, I have followed the Brandreth career with

interest, though always from afar. He condenses it on his website:

Actor, Author, Broadcaster, Former MP, Government Whip

and Lord Commissioner of the Treasury – all alphabetical and orderly

until he moves on to Awards Host, After-Dinner Speaker and the rest. I

don't know whether he still has a shop full of teddy bears, but he did

at the only time our paths crossed.

He was also on record as having

delivered the world's longest after-dinner speech. By this time I have

forgotten how long it was, but it was many hours, undoubtedly

chuckle-filled. I do know that he also demonstrated his ability to stand

on his head in a soup bowl and to take leave of his audience by walking

off on his hands. He is an engaging show-off, a pleasure to have about

the place.

But back to coincidences. Aware of my

abiding interest in the aforesaid one-time Lord Commissioner of the

Treasury, my daughter Heather telephoned me to ask whether I knew that

he was at that moment holding forth on Desert Island Discs. I

didn't, but I was pressing the button even as I thanked her for not

allowing me to miss out.

Then, having not missed, I was moved

to explore the Brandreth website – and found that after not being within

spitting distance for years, this irrepressible jester and erstwhile

evangelist of jumpers was actually going to be in Birmingham on

Saturday, January 29. Which brings me painstakingly to the coincidence:

that is my 80th birthday.

He is on the launch-pad at Birmingham

Town Hall to begin another barnstorming performance at 8 pm, by which

time I shall be 80-and-half-an-hour exactly. I won't be there, but I

shall raise a glass to him in deepest Surrey. That's where

daughter Heather has plotted a black-tie family dinner for all 19 of us.

Speech!

And, still on the coincidence trail,

senior daughter Beverly – name spelled the masculine way because at the

time of her arrival we were more aware of the Beverly sisters than of

the fact that they were making us get her name wrong – had already laid

the foundations of what is turning out to be our Brandreth Week, by

inviting us to her home in Taunton so that we shall be seeing the

beguiling Gyles at the town's Brewhouse four days earlier, January 25.

It's a sort of Brandreth on the Buses! Forty years without being near him, then he all comes at once.

Shameless shovellers

THE glories of the

stage have been with us for centuries, from Shakespeare to Shaw, via

Sheridan. Unfortunately, this arena of so many theatrical pleasures is

now beset by another

Sh. A four-letter Sh,

shovelled by the shameless.

When the now-fashionable kind of

alleged comedians first arrived on television, they presented what was

called alternative comedy. Even the least perceptive of viewers soon

realised that it was an alternative to comedy, and that we had

been beset by those who thought that to make their mark as funnymen all

they had to do was swear and blaspheme. Once obscene, never forgotten,

sort of thing.

They have now had things all their own way for years.

The virtual disappearance of education standards has ensured that the

ritual disgorging of four-letter filth is the cue for uninhibited

paroxysms among the patrons. It doesn't have to be funny: just give 'em

the F-word.

What has happened to ensure that nobody appears to be

in line to perpetuate the word-play delicacies of Dawson and the

daftnesses of Dodd?

Les Dawson is now somewhere Upstairs, doubtless still

having fun at the expense of his mother-in-law – she whose approach made

the mice throw themselves on to the traps – and it is highly unlikely

that even the indomitable Ken Dodd, born in 1928, will go on for ever,

though his current bookings run to June 2011. Mortality doesn't seem to

be in his reckoning, thank heaven.

Apart from interviewing him, I never saw Les Dawson

“live”, as they say so strangely these days. But my two meetings with

Doddy, plus pilgrimages to three of his shows, remain happy memories –

even though, like nearly every other comedian among the dozen or so of

that era I met, they presented the serious side that their loyal fans

have little cause to suspect.

The exceptions were Morecambe and Wise, with the zany

double act I got as they sparked each other off in their

Birmingham hotel room.

You don't catch Doddy on television these days. His

tickling-stick and his Diddymen, like the lethal-toothed lad himself,

have given way to the sneering, foul-mouthed stuff which, with the

connivance of those in charge of our home entertainment and who should

be ashamed of themselves, has turned the television set into a sewer

pipe and living rooms into cesspits.

It is no surprise that Victoria Wood, who burst upon

us as a pensively zany, highly-talented young writer and comedienne and

has since made her mark in serious drama, has condemned what she calls

coarse, harsh and laddish humour. Like Les Dawson was, she is a

practised pianist. He was a genius at playing wrong notes and making

them seem credible; she created joyous songs like the one with the

unforgettable Beat me on the bottom with the Woman's Weekly line.

Neither of them told crude “jokes” punctuated by blasphemy. Neither was

apt to appear as a super-cretin, apparently unable to stop swearing.

There was never any danger that either of them would

be mistaken, for example, for that latterday filth-peddler Frankie Boyle

– he whose every racist pronouncement and offensive barb at disability

is followed by the stench of self-satisfaction or a childish smirk.

Victoria Wood has now let rip at those who debase the

standards of stand-up and has expressed her belief that there is still

an appetite for the more gentle humour that once held sway. I am sure

she is right, although we have seen it virtually driven away by the

onward march of muck perpetrated by those whose smart suits do nothing

to disguise the fact that they are just overpaid oafs.

We are stuck with them because the comedy pendulum

has swung. The consolation is that pendulums do tend to swing back to

where they started – and dare we take a little hope from the fact that

Ofcom's current interest in the eruptions of Boyle has been augmented by

a wave of disgust from people offended by racist material in his

television routines?

Clearly, this is a Boyle ripe for lancing – and

perhaps all is not yet lost.

A high old time for the judge

- nearly

THERE'S a touch of The

Emperor's New Clothes about the internationally renowned zebra crossing

near the former Beatles studio in London's Abbey Road.

This is the one that was catapulted to

fame when the Beatles used a photograph of themselves crossing it on the

cover of their Abbey Road album in 1969. It now has a place on

the itinerary of tours of London and is a pilgrimage point for fans from

all over the world – to the frustration of drivers who come to an

impatient stop while the pilgrims pause to have their picture taken in

the middle of the road.

And now, it has become the first crossing to be given

Grade II listed status because it has “cultural and historical

importance” and special interest.

So hooray! But all is not what it seems. It's not

like that at all. Wrong crossing.

That Emperor didn't actually have any new clothes –

or any clothes at all – in the Hans Christian Andersen story of 1837,

having been conned by a couple of swindlers who said they would make him

an invisible suit. While the populace at large expressed its admiration

for the suit that wasn't there, it fell to a child to point out that the

Emperor was not actually wearing any clothes.

Which takes us back to the crossing – well, sort of.

The problem is that the Tarmacadam Mecca in Abbey Road, NW 8, the one

that sends pilgrims into paroxysms, is not the Beatles' crossing at all.

Celebrity status – Grade II listed status, indeed – has been conferred

on a crossing that is nothing whatever to do with the Fab Four. This is

The Great Crossing Cock-Up.

DISREGARD FOR SOCIAL HISTORY

Nobody would suggest that the Beatles didn't earn

their stripes, but these aren't they. This is what can happen when a

council – Westminster City Council in this case – shows a fine disregard

for social history and accords it second place to the needs of traffic

management.

The original crossing was removed many years ago. By

now, no original features remain in the one that has succeeded it,

several yards south. Even the council can't remember precisely why or

when it was moved – but ever since, we've all been pretending that its

successor's non-existent claim to fame is still the bee's knees, not to

say the cat's pyjamas.

Fortunately, unlike what happened with the salutary

example of the Emperor's New Clothes, no little girl loiters by the

Belisha beacon to point out to pilgrims the error of their ways.

Interestingly, news that listed status had been

accorded to a crossing that had nothing to do with the Beatles emerged

almost simultaneously with that of the death of James Pickles, the judge

who famously claimed that he did not know who the Beatles were.

He would have had a high old time, asking why it had

been decided to honour a crossing unconnected with a bunch of Liverpool

lads he had never heard of.

The best panto gag of all

THERE are not many

good, well-recognised bits of pantomime “business.” There's the one

involving wads of money, with the notes being counted repeatedly to

ensure that whoever is being given them is successfully short-changed.

There's the one involving a backless

bench whose legs are all at the same end, to ensure that whoever sits at

the other end slides onto the floor in a heap as soon as the person at

the legs end stands up. I haven't seen that for a very long time. I

assume it's been marked compulsorily absent by Health and Safety.

There's the Ugly Sister whom the glass shoe fits

perfectly – on the foot of the wooden leg she has carefully concealed

beneath her skirts.

But the best of all is the Long Plank Gag. Yes,

plank, as in Thick-as-a. You may not know it. I have seen it only once,

and I think it was in a pre-war pantomime at Birmingham's long-gone

Theatre Royal, which was always the venue of choice at our house when it

was time for a bit of It's Behind You. My parents reckoned they knew

what was good for their mixed infant and it was where I started my

theatregoing on an annual basis, aged five.

Three pantomimes came my way before the wartime blitz

that destroyed the Royal. I know that one of them was Cinderella,

because Jack Buchanan was Buttons and my abiding memory is of seeing him

peeling off a succession of all-blue suits. I'm sure there must have

been a dozen of them, but even abiding memories play tricks.

STARS OF THE DAY

Two more stars of the day who came my way were Sandy

Powell and Evelyn Laye, which almost sounds as if I have been moved to

say it in rhyme. I remember that somehow or other my parents took me to

be introduced to Sandy (“Can you hear me, Mother?”) Powell after the

show, but I have no idea what the pantomime was.

Evelyn Laye may well have been co-starring with Jack

Buchanan in the saga of the glass footwear. She was the prince of

principal boys, a bold, thigh-slapping strutter, commanding the stage

and clearly not in the habit of standing any nonsense from Dandini. I

interviewed her twice – the first time in the 1960s at her Birmingham

hotel and the second time at her London home, to mark, I think, her 80th

birthday in 1980.

All of which has led me gently away from The Greatest

Gag of All, in the show whose name I can't remember, though it was

almost certainly at the Theatre Royal. The comic came striding on, stage

left, with a plank over his shoulder. He headed purposefully for the

wings on the other side, waving as he went, while, behind him, the plank

just kept coming out of the wings, stage left, apparently endless and

apparently without support.

He disappeared, stage right, with more plank still

emerging, stage left. And still it came, filling the line of vision as

it stretched across the stage and kept going. And more. And more. I was

one transfixed mixed infant.

Then, after what seemed a joyful eternity, the rear

end came into view – supported on the shoulder of the man who had been

carrying the front end.

And that was it, the best panto gag of all time. I

wonder where it's gone to.

The return of the toffee

lobber

THERE was an officious

diktat from some anonymous jumped-up clown a while ago that sought to

ban the throwing of sweets from the stage during pantomimes. Health and

Safety was on the prowl again.

Not, as far as I am aware, that anyone

has ever been injured or even inconvenienced by a seasonal

toffee-lobber. We panto patrons don't feel the need to seek special

insurance before making our pilgrimage to Puss in Boots. And in

any case, there is little likelihood that anybody will be caused

indescribable suffering on the offchance that a direct hit is scored by

the Dame or her likeably idiot son.

It is not as if Quality Street missiles are being hurled with the meaningful venom of a cricket ball that is thrown at the stumps.

No, panto projectiles tend to be launched

circumspectly underarm, apart from those whose hopeful intent is to

reach the front row of the dress circle, where, if they actually manage

to get that far, they fall with an almost apologetic air and with no

prospect at all of ruining somebody's night out.

I suppose I have seen some half-dozen

pantomimes each season for 26 years, so it was not hard to spot that the

Dame's chucking arm had suddenly reverted to concentrating on hitching

up her Les Dawson bosom, leaving the audience to fend for itself in the

matter of the sweet supplies.

Many a raucous Twankey resorted to walking up

the gangway, carefully dispensing supposedly potential missiles safely

into outstretched hands, straight from the paper bag. Oh, the shame of

it!

Is it a bird? Is it a missile? Is it a meteorite? No, its a peppermint grenade!!!!!

Happily, I am now witnessing the return of seasonal

fun. Toffee-lobbing is back, and still with no report of irreparable

injury.

Moreover, it has signalled its return by scoring a

direct hit on a cranium of some significance – that of David Cameron, no

less. Indeed, it is reported from Chipping Norton that “one toffee

bounced rather spectacularly off the Prime Minister's head.” I suggest

that if it is all right for the Prime Ministerial noggin to become an

inadvertent toffee-stopper, it's all right for the rest of us.

Meanwhile, it just so happens that Ed Miliband has

been expressing his displeasure at people who while away the hiatus

during dinners by throwing bread rolls between the courses. It would

have done him good to have looked in at P G Wodehouse's Drones Club,

where this was a staple sport, like pinching policemen's helmets on Boat

Race Night.

Alas, he was not even born when these merry larks

were at their peak, so there is little hope of his being brought to

enlightenment and repentance at this stage. Indeed, are we on the way to

seeing the termination of toffee-lobbing being followed by a bread roll

Milly ban?

Let's have believable eating

I HAVE never tried it,

but as my only stage appearance, apart from Third Shepherd shortly

before an otherwise long-forgotten Christmas, was to whiz on as The Wind

– short blue shantung frock with serrated hemline, while crying

“Whooooo!” to make the infants-school

flowers grow – there has really been no need for me to try to eat as

part of a performance.

Somebody has probably written a

guide to eating on stage but I have not been able to find any reference

to it, so this could be a clear niche for anybody with experience.

Meanwhile, I have no idea what advice is apt to be flying about in

rehearsals as opening night approaches.

I know that the tables are always laid with plates

whose contents would not deter a fieldmouse. From what I have seen, any

sausage that is up for demolition should be chopped to a length of not

more than ¾in and every participant at the failed feast that has been

provided has clearly been warned not to come remotely near to being

caught with a mouthful and the need to utter the next line.

Cutlery clatters on plates, but with the best will in

the world we can see it's all a big tease. Uppermost in participants'

minds is the need to have a clear run at their next requirement to

speak, unencumbered by having to wedge a wodge of something edible out

of the way and into their cheeks as an essential preliminary.

Presumably, as well as remembering every line, they

have to remember the rehearsal at which they discovered how long it

takes to swallow whatever comestible precedes it. It sounds a bit of a

challenge, but if a playwright has decided to make life difficult it is

one that has to be met.

The other thing about eating on stage is that it

customarily requires a table. And the thing I have noticed about tables

is that if they have to accommodate, say, half a dozen characters, they

are often rectangular, placed parallel with the audience's seats, with a

chair at each end and four facing the auditorium, leaving empty the side

that is nearest the audience.

It may have worked for The Last Supper, and it may continue to work for accommodating the chairman, secretary, treasurer, gents' and ladies' captains et al at the annual meeting of the golf club but it looks distinctly odd onstage in something theatrical.

What it means is that the director did not want us to

be contemplating a couple of diners' backs for the duration of the meal.

But yes, it does look odd.

Would it not be better for a six-seater table to be

placed at one side of the stage, at 45 degrees to the audience, starting

stage-front and angled towards the upstage wings? Each of its long sides

could then be used to accommodate two actors, who would provide a far

more believable seating arrangement, with two of them having their backs

towards just a small section of the audience. Unavoidably, the actor at

the downstage end of the table would be ignoring the patrons on the

other side of the auditorium, but at least he would be sitting

acceptably sideways-on to most of the others.

But better still would be to have a round table of an

appropriate size. This could be placed stage-front at the centre

of the proceedings, only taking care not to seat one of the participants

to face firmly upstage with his back to the audience. Arrange the chairs

so that there is a natural-looking gap there.

And at least – again – it's food for thought.

Hairy moments

I HAVE long suspected

that any facial fungoid growth, commonly called a moustache, merely

proves that its owner can't see what's going on under his nose.

The moustache, that spiky

self-inflicted idiocy, comes in many forms: weird, waxed, rampant, bushy

or toothbrush. There is the sinister pencil-line effort that bodes

no good to anybody. What all these manifestations have in common is that

they ensure that any face that has the misfortune to be its host is

being. . . er, defaced.

Teddy, the mad pith-helmeted nephew in Arsenic and

Old Lace, is customarily to be found charging up the stairs – after

first roaring “Charge!”, naturally – behind some sort of

moustache, though definitely not one of the indelibly daft Adolf

Hitler variety. And whenever I see him, I find that my brain cell is

straying: I am aware of a swell of sympathy for the fairer sex, or at

least those members of it who have been led by Fate into sharing their

lives with Mustachioed Man.

They may have been beguiled into marrying him. Or,

increasingly in these liberated days, they may have baulked at the idea

of bothering the vicar and simply settled for creating An Item –

i.e., something held together by screws.

Whatever the cause of their coupling, the abiding

questions remain:

Do they find it difficult to acclimatise to an

unavoidable awareness of Facial Hair? How long does it take them to

become accustomed to taking the rough with the smooch? Has any of them

ever contemplated writing an autobiography entitled My Life with a

Burst Horsehair Sofa?

And what of the perpetrators of these

territorially-ambitious blots on the landscape? What gave them the idea

that they had need of a personalised soup-strainer? Can they really be

content? Are they absolutely convinced that man is Nature's last word,

when their shaving mirror shows them a latterday Mr Chad peering out of

a rampant non-flowering bush? Wot – No sense?

One of the commonest joys of theatregoing used to be

the sight of a false moustache when one half became unstuck. I have not

seen it happen for several years now, which may be an indication that

we're into a better class of adhesive – but it was at one time not at

all unusual to see a 50-per cent fall-off which merely emphasised that

the genuine article also exists only to be laughed at.

With all these odds against him, it is therefore good

to know that Mustachioed Man is fighting his corner against cancer – and

even better, to realise that battle is being joined by heroes who

hitherto have had an unscarred upper lip and have deliberately

gone out of their way to foul their features in a splendid cause.

It is time to salute these sterling citizens. One

such is my colleague Roger Clarke, who is to be found bringing on the

bristles for the battle being fought by the Movember charity -

http://uk.movember.com/ - The idea is that the rest of us should

prise open the piggy-bank and sponsor the sprouting.

Let's do it.

Home

More car consternation

THIS brain cell of mine

is working overtime – to demonstrate that it is not really working at

all. It's a shame, because I was quite a promising citizen at one time.

But now, in the space of a

recent month, I have telephoned my dentist of 25 years, listened to his

phone ring, and hastily hung up on realising that I could not remember

his name. I have telephoned my online bank, pressed buttons as

instructed, finally reached a real live human being, and discovered that

I could not for the life of me think what I was ringing about.

This prompted me to see a memory man, because I

believe in catching crises early, whether they be a brainstorm or a

broken leg. He sat me down, asked me lots of questions and scored me 99

out of 100 because he said I had beaten all his previous customers out

of sight, having fallen down, inexplicably, only on the number of

animals I could name inside a minute.

Nevertheless, my ultimate triumph was yet to come. It

came with my first visit to The Hampton Players, of Hampton-in-Arden – a

community whose High Street, as far as I could see, contains only one

shop. The occasion was the Players' production of Arsenic and Old

Lace, the wonderful Joseph Kesselring comedy from 1939 in which two

spinster sisters keep a cellarful of corpses, which they consistently

top up by ministering to lonely old men – perfect strangers – with their

potions of elderberry wine laced with arsenic, strychnine and cyanide.

It was a happy evening. Until it was time to go home.

That is the recognised time for me to discover that my car has been

stolen, as I did many years ago after I had been to see an offering at

Droitwich's Norbury Theatre. And now, it was the time when I was to be

observed, alone and palely loitering, wandering lonely as a cloud, but

in fact feeling anything but poetic, in the vast car park that serves

the complex of which Hampton-in-Arden's Fentham Hall is a part.

I kept that up for about five minutes, after which I

walked the 100 yards back to the hall, to update Players director

Maureen George and her troops while they were giving generous support to

the bar. They were very kind, very attentive. I do not walk in the same

world as mobile telephones, so I was provided at once with the means to

ensure that my wife, the police and a taxi firm were fully updated with

the situation.

Then I repaired again to the car park and took up my

station at the gate, having been assured that my lifeline to home

would be with me in 15 minutes.

It was the kindly Rooney – no, not that one – who

duly materialised as my saviour. I told him my troubles and we set off

for deepest Bromsgrove. Then, somewhere on the motorway, I had a

revelation. A Saul-on-the-road-to-Damascus moment. A blinding,

gobsmacking bit of would-you-believe-it.

I suspect that the late Saul did not respond, as I

did, with an explosive expletive invoking four-letter faeces – but he

had not spent as long as I had, looking for the wrong car. For me, it

was a sudden, noisy evocation that combined anxiety with disbelief and

new hope. The world, in the shape of my kindly driver, had to be told.

We turned about and eventually fetched up in the

environs of Fentham Hall again – where by this time there were only two

cars on view, one of them being my wife's. Hers is a small, green car.

Mine is a slightly bigger one in orange – habitually excellent for

spotting in car parks. Unfortunately, because our daughter-in-law's car

was out of action, I had entirely forgotten that I had high-tailed it to

Hampton in a small green one. I had wasted time, energy and blood

pressure looking for the wrong car.

Back home at about midnight, it was necessary to ask

the police to call off the hunt. It was time to sit up on the bed

alongside my wife while we downed a brace of soothing scotches. Then it

was time to collect my thoughts and get back to penning something

sensible about Arsenic and Old Lace.

And at about 2 am I settled down to sleep the sleep

of the just-so-relieved.

Charity began on the fifth

floor

DELIGHTED to report

that my wife and I survived the possibly unintentional excitement of

having bed and breakfast at Birmingham's Radisson hotel at Holloway

Circus, on the fringe of the city's theatreland.

Well, it was a bit unnerving. On the

recessed shelf in our fifth-floor room was an array of goodies – Crispy

M & Ms, cashew nuts, gourmet jelly beans, double chocolate biscuits,

pastilles and a bottle of wine. But these temptations were accompanied

by a notice that said, “Dear Guest, please be aware this is an automatic

system. All items moved will be automatically charged onto your room

bill. Thank you.” It was time for walking on eggshells. We were

impressed.

Terrified, but impressed.

But we were even more impressed in the first-floor

Felini restaurant – “a stylish ambience and an authentic Italian

experience with a contemporary edge”, which is a roundabout way of

saying that dinner was superb and undoubtedly up to the task of

satisfying theatregoers at a reasonable cost after the show.

One way and another, this was a visit to remember.

The advice on telephones was a lesson in itself, with a book that

contained phone charges to everywhere, and dialling codes – do people

still dial? – that occupied seven pages and went from Afghanistan to

Zimbabwe. En route was “Burma (see Myanmar)” but Myanmar had somehow

failed to slide in between Mozambique and Namibia.

The television and radio guide told us that the hotel

provided two radio channels – Radio 1, Radio 2, Radio 4 and The New

BRMB. But who's counting?

Equally intriguing were the curtainless curtain rail

in front of a bedroom mirror, the cautionary note to the effect that the

management had removed all hotel stationery, and a couple of other

references to stationery in which stationery had been misspelled.

This sounds as if I'm complaining. I'm not. We had a

splendid visit, all the more enjoyable nevertheless when we learned of

the offer of “grab-and-run breakfast in lobby area in the early morning

hours” and the fact that the only drinking glass in sight was a large

one, primarily designed for holding wine.

For me, it was also exciting, in that the

floor-to-ceiling window offered a vertiginous view of Queensway,

far below us. I'm no hero. In no time at all, I had looked my fill and

retired to the super-soft king-size bed to await the return of innards

that unaccountably seemed to have gone missing, there to sit up and

watch Aston Villa play Chelsea and somehow send them packing without

scoring, for the first time this season.

Finding the Villa on the television was particularly

appropriate in our £150 room. I had won it in a raffle at the annual

celebrity lunch of the West Midlands branch of The Journalists' Charity.

It was a prize provided by Aston Villa.

John Slim

Home

Let's hear it for the modest

monkeys

IT IS more than five decades

since the tea business turned to monkey business and PG Tips introduced

television audiences to its handful of simian superstars. Or perhaps

they were simply stars: I can't remember when it was that people who

previously had been content to be stars found themselves elevated for no

good reason to superstardom, a status which until then had never existed

and had never been missed.

Anyway, whatever the rank of the monkeys who became

the nation's furry favourites and held that position from 1956 to 2002,

the news from the enclosure at Twyford Zoo is that Jilloch, one of the

po-faced band who were flogging us PG Tips in that period, has died,

aged 34. That was not particularly old among chimpanzees, who are

frequently able to get six decades under their belts. She wasn't even

about when the commercials were launched, but she was to become a

regular as one of the children in television's chimp family.

And the other news – as far as I am concerned,

anyway, because I had never heard it before – is that the commercials

were cut off in their prime because animal welfare campaigners,

presumably even more po-faced than the artless actors they were worrying

about, finally saw their lobbying have what they deemed to be a

successful conclusion. The chimps, with their hats, their wigs, their

costumes and their teapots, were banished.

I don't know whether the killjoys were equally

successful in getting a ban on the chimps' tea parties at London Zoo, on

which the commercials were based – but Jilloch, her relatives and

friends, who had never given a public indication of not enjoying playing

with teapots and cups of tea, were compulsorily retired from TV, along

with their delightful antics, which had been supported by voice-overs by

Peter Sellers, Bob Monkhouse, Cilla Black and others.

By the time they disappeared, they had made PG Tips

the nation's top-selling tea. It was a success which, according to Neil

Dorman, curator at Twyford Zoo, had never gone to their heads. This

being so, perhaps they could have been found a new role – as unassuming

examples to the hyper-inflated egos that are a pain in the proverbial,

both among the professionals and the amateurs of the theatre business.

But it isn't strictly at all

FOR those among us who

are happy to spend non-critical hours in front of the television,

Strictly Come Dancing

is manna from heaven for

however many weeks it continues, year after year after year.

I am one of them. I can't dance, and

it is only once a year – for however many weeks – that I am drawn to the

world of spangly women in dresses whose lengths range from the

floor-sweeping to the would-be pelmet.

I like the couples, with their weekly-rising hopes

and their ultimate dismay. I am transfixed by Bruce Forsyth who most

commentators seem to believe is taking his initials too far by

continuing to proffer remarkably lame humour followed by urgent gestures

indicating that he believes his audience ought to laugh – and sometimes,

heaven help us, by a laboured explanation of why he thinks it was funny.

And I am transfixed by Tess Daly, the presenter who

fills her dresses in all the right tight places but tends to diminish

her shine somewhat when she speaks of joodges, cooples and resoolts. I

have been intrigued enough to pursue her through several internet pages,

and on one of them I discovered that she achieved the interesting feat

of being born on April 27, 1969, and then again on April 27, 1971.

But at least there was consistency in her place of

birth, which presumably is where her accent comes from. It's Stockport,

in Cheshire, famed for the cheese that is the agreeable result arising

from doing whatever's necessary to a cauldron of curds and whey – but

not, as far as I am aware, well-known for people who talk like Tess,

though in this I am presumably wrong. Suddenly, I realise I have clearly

never met anybody who hails from Stockport.

But the really intriguing thing about Strictly

Come Dancing is its title. Strictly, for a start. Volume 2 of

my Shorter Oxford Dictionary (1983 edition) does not actually

stretch itself to including strictly – though I stumbled across

stultiloquence on page 2160 in my unavailing effort to find it,

which was something of a consolation – but it makes it clear that the

adjective strict is all to do with something that is not vague or

loose and is accurately defined and admitting no relaxation or

indulgence. So at least it's a hint of what the adverb is all about.

Alll of which means that it isn't (strictly) Come

Dancing at all, because it is also about the judges, the judging,

the jeers and the jokes.

And what about Come Dancing? It sounds like an

invitation for a spotty teenager to have an embarrassing accident during

a Saturday-night hop at the village hall – admittedly, an occurrence

that was considerably more likely in the far-off nights when embraces

were part of the terpsichorean scenario because close contact was a

must, and when young ladies had not yet thought of forming a

circle and dancing round their handbags.

Here, in short, is a programme that finds me awash

with wonderment. I shall miss it when it's gone.

John Slim

See Ann the Unforgettable below

Hooray

for Ann, the

unforgettable

AS ANY properly primed parson might say,

we are here today to give praise for the life of Ann Widdecombe.

And why not? Why wait until she has risen to higher

things and may well be in no position to appreciate the . . . well, the

appreciation? The appreciation, that is, of a fascinated fan club of

early-Saturday-evening television viewers, irretrievably hooked on her

wonderfully unpredictable waltz and delighted by the determination of

her salsa and her tango.

Here is a woman whose steely resolve has never been confined to the

parliamentary responsibilities she has finally left behind her. We have

previously seen her impishly imperious chairmanship of Have I Got

News for You, but she has now been unleashed into the arena of

Strictly Come Dancing, where she has blithely called herself this

year's John Sergeant, been described by one of the judges as a flying

hippopotamus as a result of entering on wires – which made it

extraordinarily easy for viewers to forget that she was Minister of

State for Prisons from 1995 to 1997 and the Shadow Home Secretary from

1999 to 2001.

And always remember that she came pristine-clean through the

parliamentary expenses scandal, after which she was described by one

London newspaper as one of the saints among MPs.

She is a joy – because in the participants' weekly battle for points,

she is to all intents and purposes a non-starter. She is unpredictable.

She is a one-woman theatre in the round; as stately as a galleon until

she begins to dance. She was the first to say she dances like Dumbo the

Elephant, thereby leaving full-time television commentators kicking

themselves for not having thought of it first.

The former MP for Maidstone doesn't give a damn. She left Parliament in

May this year and she beams like a lighthouse on overtime. She enjoys

herself. She takes on the judges with a huge smile, then derides herself

a bit more decisively with a comment that they have omitted to make.

Having boomed through the quickstep and the waltz and achieved the

record low marks for the salsa, she then achieved that literal lift-off

in a wire-supported tango. Partner Anton du Beke said he wanted to

impress the judges, though he may simply have been cutting down on the

need for weight-lifting practice.

This is Ann the All Right. The Ann who is this year's most popular

perpetrator of personal disaster and the contestant to be publicly

acknowledged as the first to make judge Craig Revel Horwood smile. (It

was that salsa again). What

a fascinating character!

On occasions like Strictly Come Dancing, she determinedly hides

her steely side – though it did come out after one of her appearances on

Have I Got News for You, when she was clearly rattled by comedian

Jimmy Carr. She later commented: “His idea of wit is a barrage of filth and the sort of

humour most men grow out of in their teens.”

To me, there seems little doubt that here is a woman whose depths are in

the Thatcher mould and who at some point could have been a credible

successor to the Iron Lady.

But I'm not pushing it. There's far more fun for the rest of us when she

is Ann, The Flying Tango-ist.

John Slim

Printer

problem

I DON'T let many things worry me. Generally

speaking, I am happy to go on failing to understand any given situation.

But I have just realised, several years after it

first sat on my desk, that my printer is taking liberties – liberties

with me.

There are many varieties of printers but I know that

few of them have a hope of emulating the sheer cheek of my Epson Stylus

DX4000. They just push the paper through with a consistent hum, or even

with no sound at all and often far more quickly.

My printer is not like that. Not at all. Mine

talks to me, and it's rude, extraordinarily rude. Fortunately, it has

taken me until now to realise the fact. Otherwise I would have been

knocked out of my stride years ago. But at last my printer is exposed as

a shameless oaf. And between you and me, I'm not impressed.

You see, my printer, like so many others, also has a

habitual hum – but this is a hum that comes with rapid intermittent

breaks. And now that I have actually listened to it, I realise that it

is being distinctly personal. And I do mean distinctly: there is

no mistaking what it is saying.

Many years ago, there was a song called Three

Little Words. It claimed a permanent place in my brain cell because

my sister was convinced that it was Three Little Worms, which

caused her to fail to understand why the singer was asking, “What

would I give for those three little worms?” Just one of those

little mishearings that happen a thousand times a day up and down the

land, generally with no harm done.

And in all fairness, my printer is not actually doing

me any harm, either. But now that I have sat back and really listened to

it, I have to say that I'm not impressed, which I can't help feeling is

fair enough – because my printer is clearly not impressed with me,

either.

What it is saying, insistently and unmistakably, is

“Small penis, small penis, small penis.” I am the only one here,

so it's not particularly difficult to work out who is the object of this

unbridled scorn.

So far, I have not thought of a way of shutting it

up, other than by refraining from using it, a course of self-denial that

would inevitably ensure that I could not share my problem – or should I

say what my printer perceives to be my problem? – with my friends, other

than by reverting to pen and ink,

Remember letter-writing? The ballpoint pen replaced

the fountain pen that had replaced the quill and inkpot. And printers

replaced typewriters – which in my case means I have to switch off if I

hear footsteps on the stairs forewarning of the imminent possibility

that somebody is going to come in, discover that my printer is

laughing at me, and join in the general merriment.

Right now, I am comforted by the thought that in all

probability it is sitting there seething, because once it sees that

Small Thoughts is at the top of a page it knows that what follows is

destined to disappear at the touch of an email button and its scornful

services will not be required.

Unfortunately, there is always next time. And the

time after that.. Mockery is always just around the corner.

John Slim

In at the start of the Norman

conquest

BRITAIN has said its

goodbyes to the man who was its most-loved comedian – the man with whom

I found myself rubbing an unplanned shoulder more than six decades ago.

When Norman Wisdom and I were fellow-students at the

former Underwood Secretarial College in Union Street, Birmingham, I was

17 and he was in his mid-30s.

Ours was a comfortable but fleeting friendship. I was preparing for life in journalism by spending six months on a course that was teaching me the mysteries of shorthand – this was many years before an interview came to consist of simply shoving your microphone up somebody's nostrils – and touch-typing, while I awaited the summons to two years' National Service. He was there because he was in pantomime at Birmingham's Alexandra Theatre and wanted to be able to write letters to his already numerous fans by using the typewriter in his dressing room.

So it was with plain ordinary Norman Wisdom, quick with a quip but otherwise unassuming, polite and quiet – just another student who swelled to four the otherwise undistingished ranks of males among the 30-plus girl students – that I used to slip out to the nearby café at break times for a cup of tea, which I seem to remember was 2d and we took turns to buy it. It was to be his turn when tea-break time finally found me untreated and him in his dressing room at the Alex – but I suspect that he had probably bought the first round several weeks earlier, so he doesn't owe me one.

The other two in our quartet were a fairly studious teenager whose name was Bill and a fair-haired, happy strip of wind called Michael Adams. The Wisdom pantomime season was nearing its end by the time I used my new-found typing skills to send Michael an anonymous home-made Valentine card containing the immortal lines, “. . . whose muscles bulge through ancient mack and send cold shivers down my back”, which purported to come from any one of the young ladies who co-operated to ensure that it was waiting for him to discover it in his desk.

Pam Muddiman? Pat Riley? Pat Nicholls? Where are you now? I remember we found our way to the local record shop and took over a booth in which we could regale ourselves with Pee Wee Hunt's Twelfth Street Rag – vinyl 78 rpm, naturally – at no inconvenience to anybody else. Another student was Sheila Massie, daughter of Alex Massie, manager of Aston Villa who had been its right-half when I used to pay my schoolboy 9d (3p) to stand on the terraces for home matches.

The Underwood Secretarial College was presided over by its principal, Miss Samways, stern of demeanour but generous of spirit and never suspected of having a first name. She would come round the classroom to give pupils her individual attention, explaining something and then following through with her favourite phrase, “Do you see?” – except that she elided the first two words and pronounced the third to rhyme with the French for eye, which is oeil, so her condensed question emerged as “Dyuh-soeil?”

INNOCENTLY FUNNY

Those were happy days, unexpectedly shared with a man who was to find his way into the nation's heart – innocently funny, warmer than his fellow comic Eric Morecambe, less predictable than the stupidities of Michael Crawford in the days of Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em, not as aggressive as Ken Dodd; fully deserving of all the tributes that have been paid, now that he has left us at the age of 95. I saw only one jarring obituary, in which the writer went out of his way to speak up for smut in the face of a nation's sudden preoccupation with innocence.

Among all the comedians, Sir Norman – as he was to

become, while pretending to do a trademark prat-fall on being knighted –

was one of the two who actually endeared themselves to their countrymen.

The other was the diminutive Charlie Drake – curly-topped, moon-faced, a

roly-poly little man who would blink in slow bemusement at his

successive calamities and who was to suffer serious injuries on live

television with a spectacular but miscalculated dive through a bookcase.

Of all Britain's funnymen, only Drake and Wisdom were actually loved by

their fans. Only they had what any middle-aged mum would recognise as

the cuddle factor.

Happy days, indeed. And yes, I am quite sure that the

most endearing of all Britain's comedians, now enlivening his new

celestial surroundings, does not owe me a 1948-vintage cup of tea.

John Slim

A Tristram triumph is

surely on the way

I HAVE said many times over the long

years that David Tristram's Inspector Drake is a joy to be treasured.

This is a fact of theatre life that I learned remarkably rapidly,

virtually as soon as I saw him for the first time, when I turned up two

decades ago at Birmingham's Old Rep for Inspector

Drake's Last Case.

I don't know whether Inspector Drake needs a groupie,

but in me he has got one. I am devoted to him – courtesy of David

Tristram and of Alan Birch, who has been playing him on stage every time

the oppportunity has arisen for two decades and who is now about to

transfix a largely new audience on film.

Inspector Drake, The Movie is the label under

which Drake is destined to make his cinematic bow in the New Year. The

blank-faced lunacy that he wears like a bespoke overcoat will accompany

him into his as-yet-unexplored world of cinema. With all the confidence

I can muster, I now declare that he will be an instant high-powered hit.

Not that he looks or acts high-powered. No, this is a

an arm of the law that is laid-back, unhurried, unflustered; a copper

for whom a career comes copper-bottomed, safely ensconced in the special

stupidity that defies the paying patrons not to laugh in disbelieving

delight.

He was David Tristram's first pin-'em-by-the-ears

creation; the character who, aided and abetted by the po-faced Sergeant

Plod, laid the foundations of what is now the deserved reputation for

comic playwriting that Tristram has established. And now, after four

rib-tickling comedies that have taken him to theatres all over the

world, he is being preserved for ever on film.

On film, moreover, for money that is microscopic

compared with the budgets behind the high-powered products of the world

of cinema – with David Tristram behind the camera and doing the editing

as he goes, and actors from the amateur stage having a whale of a time

giving their services for the hell of it, with the bonus of something to

come if Inspector Drake beguiles, for instance, the moguls behind events

like the Cannes Film Festival and gets himself shown to a largely

unsuspecting audience of movie buffs – and this is by no means pie in

the sky.

Meanwhile, however, the idea is to show him to the

world in which he was born – the world of amateur theatre, with little

theatres given the chance to present the film to their loyal audiences,

once it has had its première at Sutton Coldfield's Highbury Theatre

Centre, some of whose members are taking prominent roles.

This is an exciting time – for David Tristram, for a

new company that brims with enthusiasm, and for the ever-increasing army

of afficionados for whom the chance to see what happens to the

ineffable idiocy of Inspector Drake when the camera's eye is upon him

cannot come quickly enough.

I make no bones about it. Having been in on the

development of Drake since his Last Case had me and the rest of

the audience wiping our eyes and doing our best not to roll in the

steeply-stepped aisles of the Old Rep, there is no cinematic experience

I would prefer. He is Inspector Clouseau-cum-Goon. He is an

unparalleled prat. He is a joy that is largely indescribable. And on

film he will be with us for keeps.

No, I am not going over the top – and disbelievers

may discover a hint of the joys that are to come by viewing the trailer

that Tristram has created for Inspector Drake, The Movie, here on

Behind the Arras. In years to come, the film may well be seen as

opening a new distinctive doorway in a medium that is waiting for a

successor to the Keystone Kops, Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, Abbot

and Costello, and Mr Bean.

The first year to come is 2011. Possibly February.

I'll be there.

Dangerous work is afoot

I WAS in church, having

my weekly kneel, when I was struck by the shoes of the woman kneeling

two rows in front. Not literally: we are a peaceable lot in our

communion, not prone to indulge very often in flinging footwear and

especially when we are wearing it.

Let me say at once that I'm sure that the owner of

the feet they were adorning was not relying on them to supply

information vital to her being able to get them correctly housed on one

foot or the other. Nor was the outsize lettering the only thing that was

on the labels, which also included, among other things, a barcode.

Nevertheless, this unexpected pause in my pensive

conversation with the Almighty did prove to be an impressive

distraction. Suddenly, for the first time, I was aware that shoes can

administer a figurative kick when you are onstage and least expect it.

It is a kick not directed at you, the actor, but at

unsuspecting audience members – particularly in a studio production. I

realised, in my interrupted silent discourse with my Maker, that in the

close-up intimacy of a studio a shoe label could easily spell the end of

concentration. Well, it would for me, anyway.

You are required by your director to drape yourself

languidly along a chaise longue. What your director did not

realise was that in honour of your first night you would be wearing your

new shoes and might well be stretching your superbly-shod feet in the

direction of an audience sitting on your level and within a few feet of

you.

SILENT SNEER

If your new shoes happen to be bearing a small but

perfectly formed adhesive banner that says Lotus or Hotter or Clarks,

and if I chance to be a member of the audience that has turned up to see

fair play, I am confident that the carefully crafted plot would lose my

attention on the instant. Even more so, if one shoe was displaying an L

and the other an R and clearly inviting a silent sneer.

I don't think that the devastating propensities of

shoe soles are sufficiently widely appreciated. For instance, when the

bride and groom kneel for the blessing at their wedding, the groom's

soles are briefly the most prominent things in church. If they are

sporting a hole, or a label that offers an interesting read, you may be

sure that they will be the talking-point of the reception. Nobody will

have missed it.

It's the same in any studio production that features

a chaise longue that is required to support any member of the

cast. The director should either position it so that the soles somehow

avoid pointing at the patrons – or, better still, every pair of shoes

that is going to be involved in the evening's proceedings should be

upturned and checked for potentially lethal labelling – because if

labels sense an opportunity for mischief they will not hesitate to grab

it.

In this, they are rather like the legend on the golf ball with which a friend was enjoying a competitive foursome. My friend was always the first to pick up his ball before moving on towards the next hole. He did not explain himself to his companions, but he told me later. His ball was the one that was stamped Reject.

John Slim

When is a channel a gutter?

INTERESTING, isn't it, how we keep on

thinking that television's obsession with “reality” programmes has

reached its nadir – only to realise that it has succeeded, yet again, in

being even more abominably base?

One of its more recent efforts, Ladette to Lady,

which seeks to glue us to the drunken excesses of a bunch of young

Australian women in a high-class English college, follows the very

resistible delights of Big Brother and other desperate

concoctions such as How to Look Good Naked, which staked much on

its titillating title.

But for sheer cynical catchpenny exploitation there

has been little to match the latest delvings of Channel 4. The premise

is that we are shown an attractive person and one who has some kind of

deformity. To ensure that the difference between them does not escape

the notice of the less fortunate one, it happens in a house with

mirrored walls.

I have not yet read anything other than a specious

reason for the enterprise, but apart from a desire to spend as little as

possible on a programme while exercising a schoolboy insistence on

appearing to be ever so brave and naughty there does not appear to be

another one.

SOMETHING ROTTEN

There is indeed something rotten in the state of

Channel 4 – which is all the more regrettable because this is the

channel that repeatedly produces documentaries of value and absorbing

interest, and whose evening news is given the time to present more

informative coverage than is available on BBC1 and ITV1. Yet, time after

time, it behaves not so much like a channel as a gutter.

And it inevitably prompts questions. Questions like,

What sort of person is it who would (a) think of, and (b) create this

kind of barrel-scraping stuff? And what is the state of mind of the

authorities that permitted it?

And what kind of unfortunate would suddenly permit

his or her misfortune, which has presumably been a lifetime's

embarrassment and regret thus far, to be blasted into the public arena

and provide a field day for voyeurism on a nation-wide basis – assuming,

of course, that the nation is of a mind to give its support by tuning

in?

And was he or she given any sort of hint about the

title of the programme that was to offer unlikely stardom to its

participants in furthering its own bid for sewer status?

It's Beauty and the Beast. “Yes,

that's what we're calling it – and you're the Beast, by the way.”

We are a wonderful nation.

Home

Pope Benny, Bromsgrove and

the bangers

MIGHT you be in the market for something different in

sociable shirts? There's one now available in white and gold. It sounds

like a combination of Spurs and Wolves, but it's nothing to do with

football fever.

No, this is a rather special creation, designed to

commemorate the imminent visit of Pope Benedict XVI to Britain. If you

plan to be among the tens of thousands in Birmingham's Cofton Park at

Longbridge on September 19, you may get a glimpse of the Pope, but

possibly not of the Popemobile. There are anxieties about the security

that would be involved in seeing it safely from Birmingham Oratory, on

the Hagley Road, to Cofton Park, scene of

many a mass strike meeting by car workers in the past.

There is, however, every chance of swooping on a

shirt beforehand. Indeed, as the newsletter of St Peter's RC Church,

Bromsgrove, helpfully points out, you can order one by calling 0844 8111

031 – and it urges you on your way with: “Be seen in the right gear.

Order your Pope Benny shirt today.” Of all the parishes in the

3,000-square-mile diocese, which covers Warwickshire, Worcestershire,

Staffordshire and Oxfordshire, St Peter's is one of the closest to what

will be the centrepiece of the Papal day. Clearly, it is not overawed by

its distinction.

Even without the Popemobile, we are heading for a

day predestined to be brim-full of theatre. The Pope will celebrate

Pontifical Mass, in the course of which the solemnity of the occasion

will be augmented when he beatifies Cardinal John Henry Newman, an

Oratory priest for nearly 40 years in the second half of the 19th

Century, who is about to take his first step towards sainthood.

I hope no pilgrim who looks up from his prayers to

point a camera at the Pontiff will find himself drummed out buttonless,

because it will be a day of which many will hope to create a permanent

record.

In addition to Cofton Park and the

Oratory, where he will see Cardinal Newman's room, the Pope will also

visit St Mary's College, Oscott, the Birmingham archdiocesan centre for

the training of priests.

Meanwhile, back at Bromsgrove and nearly two weeks

before the Papal visit, St Peter's has something else up its

shirtsleeve. The church has a celebration of its own on Wednesday,

September 8, for its 150th anniversary. This will find the

Archbishop of Birmingham, the Most Rev Bernard Longley, celebrating its

jubilee Mass – followed by a celebration buffet in the school hall.

“But”, the newsletter warns, “don't

just come for the sausage rolls.” Sausage rolls and Pope Benny, too. An

unlikely but admirable mix.

It is good to see that the human touch still

flourishes undaunted against some pretty impressive odds. All the world

is indeed a stage.

John Slim

Home

Where there's a

Will, there's a way out

AS it

prepares for its 60th

anniversary season, Hall Green Little Theatre announces that “there is a

whole lot of rebranding going on” – and the immediate casualty is none

other than the Bard of Avon.

William Shakespeare – more informally

known as Bill Wagga Dagga, I seem to remember – is caught in the act of

a sweeping bow as he appears in the top left-hand corner of the

theatre's letter-heading.

He's been there for 60 years – but not any more. No

more Will. Look your fill.

But

it is not only those taxpayers on the receiving end of Hall Green's

correspondence who will find that Shakespeare has been replaced by

hglt – none of your outmoded capital letters in its New Age

thinking. No, he is about to disappear from membership cards, audience

membership cards, diaries, theatre signage, badges, posters, flyers and

crockery.

And

presumably from programmes as well.

But

it is not only those taxpayers on the receiving end of Hall Green's

correspondence who will find that Shakespeare has been replaced by

hglt – none of your outmoded capital letters in its New Age

thinking. No, he is about to disappear from membership cards, audience

membership cards, diaries, theatre signage, badges, posters, flyers and

crockery.

And

presumably from programmes as well.

The new corporate look, designed by Hall Green

member Edward Stokes, with the idea of presenting a young new look and

in the hope of attracting new members for its diamond jubilee season,

has no room for the son of

Stratford. As he might have put it, given half a chance, exit pursued by

bear. If this saddens you, look away now.

The season

opens on September 24 with Neil Simon's Barefoot in the Park in

the main auditorium and promises to continue the “commercial” feel

throughout, with Mother Goose, Blood Brothers,The Unexpected Guest,

Dangerous Corner and Outside Edge lined up to show that Willy

Russell, Agatha Christie, J

B Priestley and Richard Harris won't be missing the party after the

pantomime.

The studio

theatre, meanwhile, is not quite so clearly intent on offering an

irresistible programme, despite its inclusion of Alan Bennett's The

Lady in the Van.

The other

productions are Four Nights in Knaresborough, through which

Paul Webb recounts his modern language version – with plenty of

profanity and slang – of the aftermath of the murder of Thomas à

Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170; Straight and Narrow,

by Jimmie Chinn; The Long Road, by Shelagh Stephenson; and an

unspecified youth theatre production.

And they'll all be launched, untrammelled by our Will. I can't help

feeling sorry for him – but I suppose he's had a good run.

John Slim

Waiting for the knock-out

Punch?

SO that's one in the eye for Mr Punch – and I

bet some readily-offended jobsworth is all aglow with satisfaction.

A fluffy mop is replacing the traditional walloping

stick – but even so, Judy is no longer going to suffer any kind of

clouting. Indeed, her regrettably reformed husband is even being

required to abandon the business of throwing away the baby. Imagine

that!

All is calm, all is not-so-bright at Spinnaker Tower,

Portsmouth, where officialdom fears that in our new age of walking on

eggshells there are some people who are going to be offended by the

sight of one puppet hitting another in the cause of pretend violence.

Perhaps there are – but that is surely their problem. Isn't it

wonderful?

It is getting on for 600 years since the seeds of

Punch & Judy were sown in

In the early 18th Century, Punch was

wowing the crowds in

Now, however, Mr Punch is being forced to face not

only his old enemy, the long-established interfering police constable,

but his upstart fellow officer, PC Political Correctness.

MOCK-MAYHEM

It's quite remarkable. Are there really people stupid

enough to take offence at ludicrous mock-mayhem on a 2ft-square arena –

possibly afterwards going home and taking the latest television

violence, real and fictional, without a blink? And if there are, are

they so extraordinarily stupid that they will be unable to resist

unveiling their idiocies to the world at large?

If this daftest of diseases spreads, Mr Punch's

famous war cry, “That's the way to do it”, will acquire a ring that is

horribly hollow. I am already aware of a distinct unease when I find

that Daniel Liversidge, the

Whatever next? Longstanding

stalwarts, the Devil and Punch's mistress Pretty Polly, suffered general